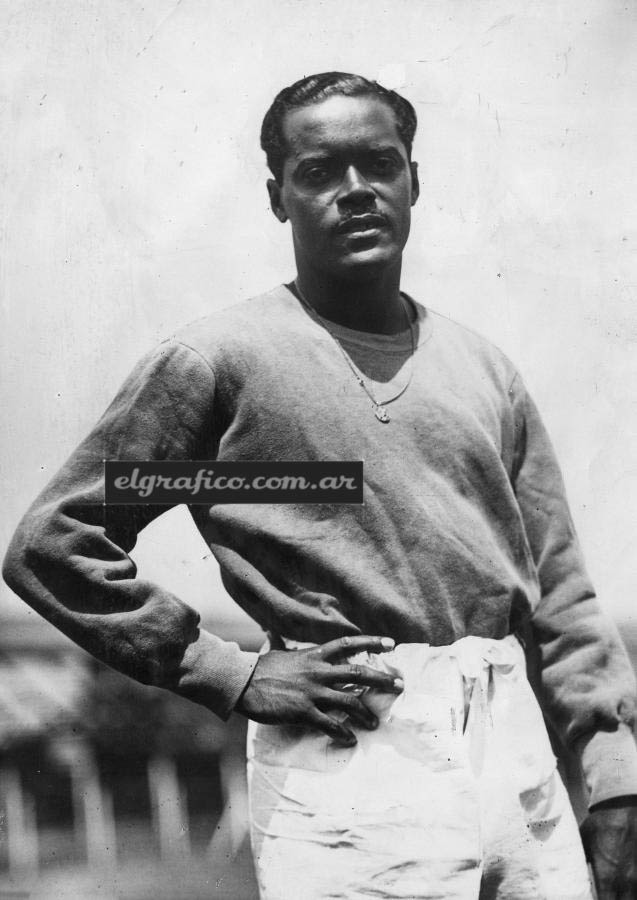

Leônidas da Silva

In 1936, Leônidas da Silva left Botafogo to join Flamengo. Already a star in the domestic Brazilian game and an established player with the Selaçao, across the next half-dozen seasons his reputation as one of the all-time greatest players from that South American cradle of footballing gods would be firmly established. Short in stature, but big in ability and goals, his talent was the kind to put fans on the edge of their seats, entertain and thrill. It’s that extra special ability that marks a player out as a world star.

Leônidas was born in Rio de Janeiro in September 1913 at a time when access to football clubs presented anything but an easy path for black players, regardless of ability. At that time football was very much an elitist sport, with its European hierarchy keen to maintain a perceived purity by limiting access along demarcated lines of class and colour. Until 1918 the Federacao Brasileira de Sports had prohibited any black players from taking part in team games, let alone joining and representing football clubs. Change came in agonisingly small steps though and, even after the prohibition ended, on into the 1920s, black players were seldom seen representing clubs in Rio de Janeiro.

By 1923 however, when Vasco da Gama won the Rio state championship with several players of various backgrounds, both in terms of class and colour, it was becoming increasingly clear that to prosper, Brazilian clubs would need to abandon their trenchant and abhorrent limits to access. This change would allow players of Leônidas da Silva’s generation to rise from prescribed obscurity to international fame. By 1933, legalisation of the professional game in Brazil was conceded, partly compelled by a desire to prevent the country’s greatest talents seeking fame and fortune elsewhere was passed and, for a 20-year-old Leônidas, despite some clubs clinging on to old ways, a door was opened.

As a precocious teenager, Leônidas had begun his career at the local junior club São Cristóvão, before moving to Sírio e Libanez, where he came under the eye of coach Gentil Cardoso, who would be an important figure in his next career step. Cardoso moved on to Bonsucesso and, the young Leônidas’ goal-a-game strike rate was sufficient to convince the coach to take the blossoming talent across Rio de Janeiro with him.

If anyone had thought that his early form would not be sustained at the new club, 23 goals in his single season with the Rubro-Anil, quickly diminished such doubts. His performances for the club saw him selected to represent Rio in an interstate game against São Paulo. For some, the selection of a still teenage Leônidas may have looked a little presumptuous, but bagging a brace in a 3-0 victory confounded the doubters and suggested a higher accolade was on the way.

It was, and later the same year he was called up for the national squad, although not selected for the starting team. That would need to wait until the following year when a debut for the Selaçao came in a game against Uruguay in Montevideo. Netting both goals in a 1-2 victory for Brazil was sufficient to both establish him on the international team, and convince Peñarol that his services would be beneficial to the club.

It was also while still at Bonsucesso that Leônidas first deployed a skill that would become his trademark. During a game against Carioca in April 1932, standing with his back towards goal a cross seemed to have drifted too far behind him for any attempt on goal. Arching his back however, Leônidas threw himself into windmill motion with his feet suddenly appearing above his head and volleyed the ball into the net. Although the true inventor of the bicycle kick remains shrouded in the mists of history, with some convinced that the technique had been deployed elsewhere in South America before Leônidas’ agility confounded the watching crowd on that April afternoon, it was the teenage forward who forever afterwards would be associated with its introduction to the world.

In 1933, Peñarol swooped to take him to Montevideo and an entrance into the professional game, unavailable at the time in Brazil. A short stay in Uruguay was successful enough as Leônidas found the back of the net 11 tines in 16 league outings for the club but, with the new legislation allowing professionalism back in Brazil now in force, the siren calls of a return home were persuasive enough to persuade the forward to return to Brazil, joining Vasco da Gama, and helping them win the Rio state championship.

With his reputation now growing, a journey to the 1934 World Cup in Italy was assured, but Europe would have to wait another four years before the full flowering of Leônidas’ would be displayed before them. A first round 3-1 defeat to Spain in Genoa’s Stadio Luigi Ferraris, meant the shortest of World Cup journeys was brought to an abrupt halt. Inevitably however, it was Leônidas who scored Brazil’s sole goal of the tournament, ten minutes after half-time. By this stage of the game however, Spain were already three goals clear and the young forward’s goal was merely a consolation and, perhaps, an hors d’oeuvre for what would follow four years later, fittingly in France.

After returning from the World Cup, Leônidas joined Botafogo securing another Rio state championship, before the move that every Flamengo fan rejoices in as, now 23 years old, and entering his prime, he joined the Rubro-Negro. It was a time of massive change for a club once regarded as one of the most elitist and reticent to change. The signing of Leônidas, one of the club’s first black players, was an illustration of the changes apparent at the club.

José Bastos Padilha had assumed presidency of the club in 1934 and began to institute the changes that would elevate Flamengo from merely being one of a number of similar clubs in Rio de Janeiro to becoming the state’s, and perhaps even the country’s, most popular club. As well as the dashing talents of Leônidas, Flamengo also acquired the services of Domingos da Guia, bringing the Brazil international defender back home after a two-year exile in Argentina with Boca Juniors. Both would become adored by the Flamengo fans as icons of the club’s success.

The following year, the Hungarian coach Izidor Kürschner joined the club, bringing a European style of disciplined play with him and, combining it with the natural Brazilian ebullience, set the stage for success, although Kürschner would not be around long enough to enjoy it. In September 1938, a game was arranged against Vasco da Gama to inaugurate the club’s new stadium, the Estádio da Gávea. By now with Leônidas delivering goals, the club’s stock was on the rise. An unexpected two-goal defeat deflated the plans though and Kürschner was dismissed. Fortunately, however, his patterns of play had been established at the club and much of the success that would had been set in motion during his time in Rio..

Despite the legalisation of professionalism in 1933, a number of clubs in the Rio state had declared against the change, stubbornly hanging on to their amateur status and the self-aggrandisement that came with it, creating a split and two leagues in the state. Five years later the tide of reality had swept such reticence away and the two leagues combined. Flamengo had been part of the professional Liga Carioca de Football, but despite competing in a weakened format for five years, had failed to win a state title for a dozen seasons. That would now change. Before that however, Leônidas had unfinished business with the World Cup.

The fame and reputation of Brazil had hardly been enhanced by their route to France, as the withdrawal of Argentina had sent the Selaçao across the Atlantic without having to kick a ball in anger. The reputation of Leônidas hardly needed further promotion however, and he landed in France as one of the most eagerly anticipated arrivals. Brazil’s opening game was played on a rain-sodden pitch at Strasbourg’s Stade de la Meinau, and Leônidas quickly proved that reports of his prowess were certainly more than mere hubris.

With his Flamengo team-mate, Domingos da Guia, alongside him, playing as the centre forward of the Brazil team, he opened the scoring after just 18 minutes. The game had any number of twists and turns to come though. By the break, Brazil led 3-1 but at the end of 90 minutes the scores were back level again at 4-4.

To crash out at the first time of asking in successive World Cups was now unthinkable to Leônidas, and three minutes into extra-time he put Brazil back ahead. The goal was remarkable for being scored wearing just one boot. By this time, pitch had turned into a mud bath, with the cloying surface only reluctantly relinquishing its hold on players as they trudged wearily on. As Leônidas closed in on the Polish goal, the mud refused to release his right boot, clinging desperately to it like a spurned lover. It tore clear of his foot and he ran to score in his stockinged foot. Fortunately, with Brazil playing in black socks, and the mud covering Leônidas’ foot, the missing boot was not noticed by the referee, and the goal was awarded. Ten minutes later, he added his hat-trick goal, this time fully shod, and a later Polish goal was insufficient to redress the balance. Brazil prevailed 6-5 thanks to Leônidas’ goals, and Poland went home.

The victory sent Brazil into the last eight to face Czechoslovakia at the Parc Lescure in Bordeaux. If the first contest had been full of goals, this was one full of controversy – plus goals and outrageous skill by Leônidas, of course.

Inside ten minutes, Brazil were down to ten men when Zezé Procópio was dismissed by Hungarian referee Pál von Hertzka. In typical Leônidas fashion however, the iconic forward put the Selaçao ahead on the half-hour mark. It was a lead the ten men held onto until midway through the second-half when a hand ball in the area by Domingos da Guia, allowed Oldřich Nejedlý to equalise from the penalty spot. Despite extra-time being played, there were no more goals, but plenty of other action.

On the Czech side, goalscorer Oldřich Nejedlý left the field after reportedly fracturing an arm, and skipper and goalkeeper František Plánička broke a leg, but heroically stayed on the pitch. For Brazil, both Leônidas and Perácio Brazil were compelled to leave the field injured and, with the Brazilian Arthur Machado and the Czechoslovak Jan Říha both sent off in the final minute of the regulation 90, and no substitutes allowed for the injured players, it’s interesting to contemplate how many were left on the field to contest the closing minutes of the game.

In a game that resembled a battlefield there was one moment of mesmerising action when Leônidas attempted a shot with his trademark bicycle kick. Never having seen such extravagance previously, it initially left Von Hertzka confused as to whether the technique was within the laws of the game, and afterwards, Paris Match mused over the incident, suggesting that, “Whether he’s on the ground or in the air, that rubber man has a diabolical gift for bringing the ball under control and unleashing thunderous shots when least expected.”

Two days later, in the replay, Leônidas scored, more conventionally, to equalise Kopecký’s opening goal and, five minutes later, Roberto scored the winner to put Brazil into the semi-finals of the World Cup, and a mouthwatering contest against the reigning champions, Italy.. The physical endeavours against the Czechs would exact an expensive price though. Despite scoring in the replay, the injuries sustained by Leônidas would prevent him from facing the Azzurri. Without their star forward, the Selaçao would lose out 2-1 to the Italians, who would go on to retain their title.

Returning for the play-off game against Sweden to decide third place, Leônidas posed the question as to how different things would have been against the Azzurri had he played. He scored twice against the Swedes as Brazil ran out 4-2 winners to secure the bronze medal. The goals elevated him to top spot in the goalscoring table, securing both the FIFA World Cup Golden Boot and FIFA World Cup Golden Ball. His selection in the tournament’s all-star team was the most obvious of calls.

Back home, glory followed for Leônidas with Flamengo as they won the Campeonato Carioca, finishing three points clear of Botafogo. It was their first state title for 12 years and set the foundations in place for a team that would go on win the title three times in the following decade. His time wearing the famous red and black shirts of Flamengo was however coming towards an end, just as it reached its zenith. In 1941, he was convicted of forgery, and attempting to avoid compulsory military call-up, leading to an eight-month prison sentence. He wouldn’t play for Flamengo again,, and would later move to São Paulo where he would play until 1950, retiring at 37 years of age.

Across the years, many Brazilian forwards have been lauded for their play. The likes of Pelé Jairzinho, Romário, Ronaldinho, Ronaldo, Zico and Garrincha are names that trip of the tongue leaving the sweetest of tastes. In another era, one where a global television audience could have delighted in the exploits of Leônidas da Silva’s extravagant skills, he would surely share a place with them in the pantheon of Brazilian superstars. Sadly, that wasn’t to be the case. For fans of Flamengo however, he will always be one of the country’s greatest stars.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘These Football Times – Flamengo’ magazine)

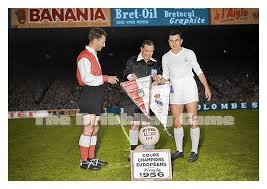

The Invincibles v The Invincibles – Hungary and Uruguay in the 1954 World Cup

The history of the World Cup is replete with tales of epic encounters. In 1950, Uruguay drove an ice-cold dagger into the footballing heart of Brazil when they lifted the trophy after beating the Seleção in the infamous Maracanazo. Twenty years later West Germany faced Italy in the 1970 semi-final as the two teams slugged it out like exhausted heavyweight boxers across a merciless 30 minutes of extra-time under the relentless Mexican sun. A dozen years later, the Azzurri featured in that epic contest against the Brazil of Socrates and Zico. In the same competition the gloriously artistic French team of Platini, Girese, Tigana et al, were denied by the Teutonic efficiency of West Germany, aided by the scurrilously unpunished aggression of Toni Schumacher.

Few of those games can, however, match up to the star billing that lit up the game when the World Champions, and undefeated holders of the crown for some 24 years, faced up to the 1952 Olympic Champions, a team on an unbeaten run of three-and-half years, almost 50 games and averaging four goals per game. It wasn’t Superman v Batman, or the Avengers Civil War, but it was getting there when, in the 1954 World Cup, Uruguay faced Hungary.

The early stages of the tournament had already indicated the sort of form that the Hungarians, so many people’s strong favourites to lift the trophy, were in. The previous year, they had visited Wembley and inflicted that humbling 3-6 defeat on the team that considered itself invulnerable to foreign opposition when playing at home. Then, in the final game before the tournament began, the Hungarians franked that form and underscored the new world order by thrashing England 7-1 in Budapest. It was the sort of form they carried into the tournament. In just two group games they amassed no less than 17 goals, defeating South Korea 9-0 and then West Germany 8-3, although the Germans would take revenge later.

Uruguay had suffered the relative humiliation of finishing in third place in the 1953 Copa America, when an unexpected defeat to Chile had cost them a place in the final. They still retained many of the players who had been successful in retaining their crown in Brazil four years earlier though, including forward Juan Alberto Schiaffino, soon to become subject of a world record transfer fee when moving from Peñarol to AC Milan following the tournament’s end, and their dominating centre half and captain, Obdulio Varela. The World Cup offered Uruguay an opportunity to reassert their global supremacy. The South Americans had been a little recalcitrant in comparison to the goal glut of the Hungarians, amassing just the nine goals in their couple of group games. Scotland felt the sharp edge of the South Americans’ frustration, conceding seven times without reply after Czechoslovakia had restricted La Celeste to a mere two strikes.

In the quarter-finals, the Hungarians scored another four goals, conceding two in reply against Brazil in the infamous Battle of Bern, and the Uruguayans matched the Magical Magyars toll when facing England in their last eight tie, albeit in much less rancorous circumstances. It meant that when the two teams faced off with each of their pedigrees looking like a CV that any team would die for, Hungary had won their three games by scoring 21 goals, an average of seven per game, and conceded five, two of which had been late goals by the Germans when trailing 7-1 and 8-2. The World Cup holders had scored 13 times in their three games and conceded just three times. In fairness though, this World Cup tournament was hardly a study in defensive expertise, with goals flowing. In the quarter-finals, Austria defeated Switzerland 7-5, after being three goals down, before losing to West Germany 6-1 in the semi-finals. By the time the two behemoths met in Lausanne’s Stade Olympique de la Pontaise, on 30 June, the 45,000 spectators were expecting to be royally entertained. They wouldn’t be disappointed.

As well as a contrast between two teams, each with arguably logical claims to being the planet’s foremost footballing power, the game would also inevitably feature a clash of cultures as the South American pattern of play rubbed up against the dynamic Hungarian system. At the time, with intercontinental travel still a major problem there was precious little interaction between teams from the different continents and World Cups were serially won by teams from the host hemisphere. Brazil’s victory in Sweden at the 1958 tournament was the only time this trend was bucked, arguably until Brazil’s 2002 victory in Japan. There was therefore still a measure of mystery when teams clashed in this manner.

The Hungarian pattern, playing with what has latterly been termed as a ‘False Nine’ usually in the guise of the astute Nándor Hidegkuti, predating any kind of assumed tactical genius of Guardiola’s Barcelona around fifty years later, was a key innovation. The ploy created space in the midfield and fluid attacking options. Although the tactic invariably provoked problems for opponents – not least England whose defence had been torn asunder by the rampant Hungarians – the Uruguayans had the players with flexibility to counter the move. Varela would be absent through injury, and replaced by Néstor Carballo who, similar to his captain would not feel out of place advancing to close down a deep-lying opponent.

Hungary were also denied the services of their captain, with Ferenc Puskás also on the injured list. His absence however did allow coach Gusztav Sebes to bring in Peter Palotás, who had played in the Hidegkuti role. As the two dropped deeper, space was opened in the middle for the likes of Zoltán Czibor to exploit, with the Uruguayan centre half drawn out of position. It would lead to the opening goal of the game, as the rain poured down, slicking up the playing surface.

In their previous three games, Hungary had been quick out of the blocks to try and establish a domination of the game and an early lead. Against South Korea, Puskás had scored after a dozen minutes, Consequential games would make that strike appear tardy. Against West Germany Sándor Kocsis had netted the first of his four goals of the game with just three minutes on the clock. The early strike rate was then maintained against Brazil as Hidegkuti gave the cherry-shirted Europeans the lead after four minutes. It was a ploy that Sebes insisted on against Uruguay as well.

In the Uruguayan goal, Roque Máspoli, was in for a busy first dozen minutes or so. First Palotás tested the vastly experienced Peñarol goalkeeper drawing a sharp save from the 36- year-old, and then Jozsef Bozsik, standing in as skipper for the absent Puskás, and somewhat controversially allowed to play in this game despite being dismissed in the battle against Brazil, fired narrowly wide. The nearest to an early goal came from Hidegkuti. Shooting from a tight angle, his effort scraped past the post with Máspoli beaten and Czibor in presumptuously celebratory mode, before reality and anguish subdued his ardour.

When the twelfth minute arrived without a breakthrough for the Europeans, Uruguayan coach Juan Lopez may well have been relieved as his side eased their way into the game, but a goal was imminent. The deep-lying Hidegkuti had found his usual parcel of space in midfield and picked out Kocsis with a neat lofted pass. Spotting the penetrating run of Czibor, the Honvéd forward who would later escape the invasion of his country by the Soviet Union to achieve legendary status in Barcelona, nodded the ball into the Uruguay penalty area for his team-mate to run onto. With his marker befuddled by the move, Czibor collected and shot from around 12 yards. His effort was scuffed however and surely should have been saved, but somehow Máspoli contrived to allow the ball to bobble past his outstretched hand and into the net. The Hungarians were ahead.

Perhaps sated by the strike or lulled into a false sense of security by the memory of how so many of their opponents had folded after falling behind to an early goal, and undoubtably to Sebes’s great chagrin, the Hungarians seemed to ease off from their busy start and Uruguay found a way back into the game. In contrast to the Hungarians fluid play, the South Americans sought to open up their opponents’ back line with astute passes and runs into space. Now with more possession than in the opening period, Uruguayan compelled the defensive pairing of Mihály Lantos and Gyula Lóránt to demonstrate their calm assurance, although they were often compelled to merely hack clear under pressure, and goalkeeper Gyula Grosics was frequently required to advance from his line to follow suit when passes evaded the duo. Probably the best chance to equalise fell to Schiaffino when he managed to go around Grosics in the area, but then failed to get off an effective shot.

After the ebullient opening from Hungary, the game was now fairly even as Uruguay pressed to level. The Hungarians lacked little in comparison though and their intricate play opened up chances as well. A goal for either side would be crucial in the way the fortunes of the game swayed back and forth. It nearly came when a cross from the left found Kocsis unmarked around ten yards from goal. His header was powerful but poorly directed towards the centre of the goal, and Máspoli leapt to divert it over the bar with his left hand. There were no more goals before the break and both teams retired to their dressing rooms to take on board the words of wisdom from the respective coaches.

Uruguay began the second-half, but if Lopez had emphasised the importance of not conceding early again, the advice was not heeded. Honvéd winger László Budai had been selected to play in place of the injured József Tóth, and during the first period, his pacey and tricky runs down the flank had been a thorn in the side of the Uruguayans, but inside 60 seconds of the restart, his play brought some tangible reward. A cross to the far post found

Hidegkuti hurling himself forwards to head powerfully past Máspoli and double the lead. Clearly shaken by the setback, Uruguay were like a dazed boxer on the ropes as Hungary pressed for another goal that would surely kill off the game. Shots rained in, but in contrast to his early error for the opening goal, Máspoli defied all of their efforts, and kept his team clinging on to a fingertip hold in the game. A penalty claim for a clumsy challenge on Hidegkuti looked to have merit, but Welsh referee Benjamin Griffiths was unconvinced.

Slowly clearing their heads, Uruguay demonstrated the resilience and refusal to bend the knee under the severest pressure that had seen them come back from a goal down in front of nearly 200,000 wildly partisan Brazilians in the Estádio do Maracanã four years earlier. Even without the driving force of their absent skipper and totemic leader, Varela, this was a team of character and no little ability. They were undefeated reigning champions of the world. With the elusive and slippery skills of Schiaffino becoming more of a factor as the game progressed and energy levels dropped, Uruguay showed they were anything but a beaten team, and with 15 minutes remaining, a Javier Ambrois pass eventually found chink in the Hungarian back line and Juan Hohberg strode forward to coolly slot home and bring his team right back into the game. Although born in Córdoba, Argentina, Hohberg was a naturalised Uruguayan and as his shot rolled past Groscis’s left hand and into the net, the whole nation celebrated that fact.

It was now game on, and for the remaining minutes, the Hungarian defence would be put under increasing amounts of pressure. Despite their flowing forward play, defence was often the disguised Achille’s Heel of the Magyar team. Usually their forwards would score more than they conceded to minimise the effect of the less than perfect back line, but in Uruguay, they were playing against anything other than ‘usual’ opponents. Schiaffino was now in his pomp, prodding and probing for any other gap that could be exploited as the Hungarian defence battled to retain what had looked like a comfortable winning position.

With just four minutes remaining, the dam finally broke as Hohberg again found space to break into the area and dribble around Groscis. Racing back to defend however, both Lantos and Jenő Buzansky had took advantage of the delay caused by the goalkeeper’s challenge to drop back onto the line. Calmness personified, Hohberg merely paused before picking his spot high into the net beyond any despairing challenge. Hungarian head in hands. Uruguayan arms raised in both relief and celebration. It would surely be extra-time now with the South American wave of momentum poised to wash Hungarian dreams away.

With both teams comfortably winning their earlier games, albeit somewhat violently for the Europeans in their game against Brazil, neither team were used to being extended into an extra thirty minutes to decide a game. In such circumstances it is often resilience and resolve that decides the issue, rather than any particular outstanding piece of skill. With the reigining champions feeling that the game was there for the taking, they continued to press and Hohberg nearly completed a hat-trick when his shot deceived Groscis before striking the post. Even then, the goalkeeper was compelled to recover and throw himself forward to block a Schiaffino follow-up and divert the ball for a corner with his feet. Hungary were forced to replicate the application that Uruguay had shown when two goals down and the game seemingly slipping away from them. There’s a time for effervescent forward paly, and there’s a time to lock down and reassess. For the remainder of the first period of extra-time, Hungary opted for the latter. The decision would serve them well.

Daniel Passarella – El Gran Capitán

To be considered an iconic presence at any club is, by definition, a rare distinction. To do so at one of the world’s leading clubs is another step or three beyond that. It requires not only a dedication to the club and its fans, a longevity and history of success in a number of roles, but also that quintessential affinity with what the club represents. Few achieve such hallowed status. Without fear of contradiction however, it’s safe to say that Daniel Passarella has such a presence at River Plate.

The player who would become known as “El Gran Capitán” and spend ten years wearing River Plate’s famous colours, another six as coach and then serve as president of the club, as well as being a World Cup winning captain and coach of the national team, was born in the Buenos Aires province of Chacabuco on 25 May 1973. His footballing career began with Club Atlético Sarmiento, then in the third-tier of the Argentine league structure. Given how his future would pan out, it’s strange to note that Passarella’s family was very much Boca-orientated and, legend has it, he once assured his Boca supporting grandmother that he would be part of a team that would destroy Las Gallinas –a nickname meaning ‘hens’ and often used as a derogatory term for River Plate. Nevertheless, in 1974, he left Club Atlético Sarmiento, and entered the Estadio Monumental as a River Plate player, beginning an association that would span four decades and see him achieve legendary status.

Passarella’s talent had been spotted by River’s network of scouts and brought to the attention of the then coach Néstor Rossi. Suitably impressed by both his organised and no-holds-barred defending, plus an ability to drive forward from the back and score, Rossi persuaded the young Passarella to put aside youthful enmities and join River. The blandishments of the coach endured, and a 20-year-old Passarella crossed the Rubicon. As if to underscore the break with previously held emotional attachments, his debut in a pre-season game would be against none other than Boca Juniors. It’s not known what his grandmother thought of the occasion.

Although making his league debut that same season, Passarella would quickly become a regular starter, and begin the climb to greatness, when River’s record goalscorer, Ángel Labruna replaced Rossi for the following season. With Passarella inserted into the spine of the team, along with signings brought in by the new coach, the club was set for a golden period. River had last won the Metropolitano title in 1957, the year after Passarella had been born. It had been the club’s 13th and, some considered, ill-fated title, but all of that was about to change. Playing from centre- back, Passarella would appear in 29 league games that term, scoring an impressive nine goals, as River secured the title, four points clear of Huracán, with Boca a point further back. Although far from being the league’s top scorers, River’s defensive efficiency with Passarella at the heart of things returned the best record, conceding just 38 times, and losing a mere six of the 38 fixtures. The stage was set.

Despite standing a mere 1.73metres, much as with so many other great defenders of the era, he played as if he was two metres tall. Short in stature, but still a giant in the air, he seemed to defy the limits imposed by his short frame, consistently dominating forwards despite conceding height to them. Professional to the core, he would deploy all legitimate means to prevent his team conceding, and never shirk from indulging in the darker arts of the game if the situation required such things.

Strong and dominant with pace aplenty, his determined attitude saw him rarely lose out in the intensely physical battles of the Argentine league. As if that were not sufficient upon which to build a reputation however, his early ability to score goals would hardly diminish as his career progressed. Across his two terms with the club, developing a polished technique from the penalty spot and dead ball scenarios, he would score 99 league goals for River across 298 games. An average better than a goal every three games is a decent return for many strikers, but here was the most consummate of defenders offering up the most productive of bonuses. His talent received due reward when he was named Argentina’s Footballer of the Year in 1976. He was still only 23 years old.

Very much in the way of Passarella, River were elbowing their way back towards the top table of Argentine domestic football and when the squad for the home World Cup in 1978 was announced, alongside club mates Ubaldo Fillol, Roberto Perfumo, Reinaldo Merlo and Leopoldo Luque, the name of Daniel Passarella was at the top of the list, with the captain of River Plate also granted the honour of leading the national team. His debut had come during a 1-0 victory over the Soviet Union in a friendly in Kiev on March 20, 1976, and a little over two years later, on 25 June 1978, in River’s own Estadio Monumental, more than 70,000 celebrating Argentines saw Passarella become the first Argentine to list the World Cup.

The trophy was handed to Passarella by General Jorge Rafael Videla, head of the military junta ruling the country. The regime was responsible for tens of thousands of deaths during the years of harsh military repression, and the Argentine captain would later lament that, “If I’d known then what was happening, I wouldn’t have played at all.” Cynically perhaps, some would argue that it’s easy to say that in retrospect, but sitting in the comfort of a democratically run country, such superior opinions can come too easily.

Domestic success continued. The Nacional title was won in 1975, 1979 and 1981, along with other Metropolitano successes in 1977, 1979 and 1980. The goals also continued to flow. In 1976, he scored a staggering 24 goals in just 35 league games. Despite River’s success and playing for one of the country’s top teams, it was still a phenomenal scoring record for a defender. Despite his goals, frustratingly, it was Boca who picked up both the Nacional and Metropolitano titles that term.

By the time of the 1982 World Cup, Passarella was a prime target for the top clubs of Serie A and after Argentina were eliminated from the tournament, Fiorentina moved in with a bid to take the River Plate legend to Tuscany. He would be joined by Brazilian legend and skipper Sócrates, although reports suggest that the pair were anything but close. Given the traditional rivalry between the national teams of Brazil and Argentina, it’s perhaps little surprise that the captains of each of those sides were hardly the best of friends.

Across the next four seasons, Passarella would average 35 games a season with I Viola, scoring first three, then eight, followed by nine and, in his final term there, 15 goals. Although never good enough to challenge for the Scudetto in any consistent way, Fiorentina did qualify for UEFA Cup competition in 1983-84 and 1985-86. In the latter of those seasons, his last with the club, Passarella’s return of 15 goals is made even more remarkable by the fact that the total was more than half of the club’s entire haul of league goals. He would leave Tuscany after the 1986 World Cup, having played 109 games for Fiorentina.

Although a triumph for his country, the 1986 World Cup constituted a personal disappointment for Passarella. Chosen for the squad, a bout of enterocolitis saw him miss the tournament’s action. He was replaced by José Luis Brown who scored the opening goal in the World Cup Final. After the tournament, rumours broke out of a rift between Passarella and Diego Maradona. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, coach Carlos Bilardo sided with his star player and Passarella felt that the two combined to keep him out of the action.

Whatever the truth of that, or otherwise, it illustrated the undiminished burning ambition of Passarella to play, and win, at the highest level of the game. Despite not kicking a ball in the tournament, his presence in the squad ensured him of the exclusive honour of being the only Argentine to feature in both of his country’s World Cup victories. As with 1982, the end of the World Cup saw another move, and Passarella left Tuscany journeying north to Lombardy, and joining I Nerazzurri of Internazionale.

His first term at the San Siro saw Inter hit a third-place finish in Serie A, a point behind runners-up Juventus and four astray of the champions, a Diego Maradona inspired Napoli. The rivalry between the two Argentines, added to by the discomfort of relations at the 1986 World Cup, would only have made losing out to his compatriot’s club even more bitter for the defender with the burning desire to win. Nineteen eighty-six, also saw Passarella play his last game for Argentina, after 70 caps and a highly impressive 22 goals. It’s a goal ratio better than that of Spain’s Fernando Torres! The following season would see Inter trail off into fifth place and despite Passarella delivering his customary goals there seemed little chance of the club enjoying league success, as stadium-sharing rivals AC Milan took on the mantle of Italy’s top club.

Passarella was now 35 and with the remaining years of his career slipping away, he sought a way home, returning to Buenos Aries and the Estadio Monumental. He would play just one further season with River, finishing a disappointing fifth in the league, some 17 points adrift of champions, Independiente. In December 1989 though, another chapter in the career of Daniel Passarella would open when former team-mate, and now River Plate coach, Reinaldo Merlo resigned his post. With their legendary captain and national hero now back home, there was an irresistible clamour for Passarella to inherit the job, and El Gran Capitán swapped the white shirt with the red sash for a tracksuit and position on the bench. If Passarella’s ascent to the realms of playing for River had brought success to the club, his time sitting in the coach’s dugout would hardly suffer by comparison.

The 1989-90 Primera División season had hardly been an encouraging one for River, hence Merlo’s departure. When Passarella assumed charge of the team’s affairs, the club were languishing, comfortably adrift of table-topping Independiente. By the time the last game had been played though, River had eaten away at the deficit and built a seven-point cushion to the club from Avellaneda. River had won the title and conceded a miserly 20 goals in the 38-game league programme. Passarella organised his team to play in the same way he had when wearing the shirt. Cold-eyed and determined, win at all costs and tolerate nothing less than success. It was immensely successful and as the Argentine league system was split into two halves, the club secured two more titles. River Plate was now on an upward trajectory, but Passarella wouldn’t be there to enjoy the full fruits of his labours. A string of other coaches would reap the benefit as the club added a further three Aperturas and four Clausura titles. Somewhat ironically, the success that he helped to create that meant that, after he left the national team four years later, an immediate return to River was hardly possible.

The 1994 World Cup was staged in the USA and, much as with the fate of Merlo at River Plate, the downfall of another hero would herald a call for Passarella. Argentina were eliminated by Romania and a failed drugs test also brought the international career of Diego Maradona to an end. Coach Alfie Basilo was moved out and when the question was asked as to who should be invited to take over as coach of the La Albiceleste, there were few dissenting voice from the acclaim for it to be former World Cup winning skipper and the man at the heart of River Plate’s revival, Daniel Passarella.

His first game in charge saw an upturn in fortunes with a 3-0 victory over Chile, and Passarella’s disciplinarian and demanding ethos brought similar results to those enjoyed at the Estadio Monumental. In 1995, Argentina reached the quarter-finals of the Copa America held in Uruguay, before being unluckily eliminated by Brazil on penalties, following a 2-2 draw. The following year, he guided the team to the Olympic Final, but lost 3-2 to Nigeria after twice being in front, and Argentina had to settle for silver medals.

In February 1997 Passarella’s disciplinary approach both off the field – no long hair, and on the field – adherence to positions led Fernando Redondo to announce that he would never play for the country again whilst Passarella was coach. It’s easy, of course, to find a coach’s approach unacceptable when the results are falling just short, but it’s interesting to contemplate whether, had the Brazil and Nigeria results gone the other way – which they so easily could have done – would Redondo have been happy to visit the barbers and stick to his allotted role in the team? Passarella had little time for regret anyway, declaring after Redondo’s announcement that, “If I select a player who thinks he’s doing the team a favour by joining us, then I not only irritate myself but my players, as well.”

Five months later, Argentina again fell at the last eight stage of the Copa America, this time, somewhat embarrassingly to Bolivia, although Passarella had selected a number of back up players. There was redemption later in the year, as qualification was achieved for the 1998 World Cup to be held in France. The following April, Passarella finally managed a victory over Brazil after 20 years of trying, returning to Argentina with a 0-1 win gained at the Maracana. It’s the sort of victory that adds lustre to the reputation of any coach. Two months later, Argentina were eliminated from the World Cup by Holland, and Passarella resigned.

At the time, River were still enjoying success and, had there been any thoughts of returning to coach the club he had served for so many years, they had to be shelved. Instead, he took up the job of coaching Uruguay in 1999, but only stayed there briefly, leaving after a mixed bag of World Cup qualifying results early in 2001, and frustration over not being able to gain the release of players from Uruguayan clubs. In November, he returned to Italy and took over at Parma, but it was both a disastrous, and mercifully short tenure. Five games and five defeats led to him getting the sack before Santa Claus had even thought about setting to work on his. Two years in Mexico with Monterrey brought a Mexican league title before a short stay in Brazil coaching Corinthians. As with Parma however, the results were poor and the sack followed in a matter of a few months, before the almost inevitable return to River.

On 9 January 2006, he returned to the Estadio Monumental, once again replacing Reinaldo Merlo. His earlier success however was not easy to repeat and on 15 November of the following year, he resigned after losing a semi-final of the Copa Sudamericana to local rivals, but always seen as an inferior club, Arsenal de Sarandí. The following summer there was wide expectation that Passarella would return to Monterrey after his success there, but the job went to Diego Alonso, and the former River player and coach had eyes on a bigger prize.

With River enduring a financial crisis and results sliding Passarella stood for election as president of the club, and swept to victory, comfortably unseating José María Aguilar in 2009. Success would not follow this appointment though. River’s on-field fortunes continued to decline, and the club endured the previously unthinkable humiliation of relegation to the Primera B Nacional. The pain of relegation was clear in Passarella’s words. “I never imagined that we would play in the Second Division. But the only person responsible is José María Aguilar,” he explained in an interview with ESPN Rivadavia radio. “My glorious and beloved River Plate … This is the second greatest pain of my life,” he declared, offering an emotional reference to the death of one of his sons in 1995. Unsurprisingly, coach Juan José López was hastily ushered out of the door and replaced by Leonardo Ponzio, who guided the club back to the top tier at the first attempt in 2012-13.

At first, it looked as if the Passarella magic had retained its power. After taking over a club in decline, things were heading in the right direction again, but a storm was brewing. In 2013, a financial investigation suggested an involvement in irregularities and alleged illegal payments. With River almost 400million pesos in debt and running at a substantial loss, the buck stopped with the president, and Passarella declined to stand for re-election. Too many, it seemed a sad end to his association with the club, but perhaps doing whatever it took to achieve success at River was just something that Daniel Passarella was destined to do.

Did the last few years of Passarella’s association with River Plate diminish his standing with the club’s fans. It hardly seems likely. Football fans can forgive many sins, especially those that appear to have been committed in the best interests of the club, no matter the folly of them. The enduring image of the man who gave so much to the club instead will surely be that of the player and coach who delivered success. The legacy of El Gran Capitán.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘These Football Times’ – ‘River Plate’ magazine).

Dancing shoes and explosive goals – The varied career of ‘Dinamita!’ Joffre Guerrón.

If asked to suggest the greatest players to emerge from South America this century, very few, if any, would raise a hand to make a case for Joffre Guerrón. Perhaps however such lack of recognition would be inappropriate. Despite often being regarded as merely one of the better, rather than greats, of his era, he was twice lauded as the MVP of the Copa Libertadores, South America’s premier club tournament. Such rare accolades that fall to very few once, let alone twice. Continue reading →

Paul Lambert – Forever the Scottish brick in Dortmund’s Yellow Wall

For any footballer at a mid-ranking club, bereft of the sort of the perceived talent and reputation that attract admiring clubs like moths to a light, and a defunct contract, there’s an obvious fork in the road. To the right lies the safe path. Your club wants to offer you a new deal. It’s safe. It’s guaranteed. It means you can still provide for your family. The other road – the one leading to all sorts of left field possibilities – is solely reserved for the brave, or the foolhardy. It leads to, well that’s the whole point. You simply don’t know where it leads, and if your briefly itinerant excursion into the exploration of the unknown is a dead end, there’s no guarantee that you can retrace your steps and opt for the other road afterwards.

Such a choice faced Motherwell’s Scottish midfielder Paul Lambert, at the end of the 1995-96 season. Lambert chose left path, having “…always wanted to try to play abroad.” As he later remarked, “I had nothing to lose at the time and never knew how things were going to pan out.” Sometimes the right path is the wrong path. Lambert chose left and twelve months later with a Champions League winner’s medal in his pocket after a Man of the Match performance negating the talents of Zinedine Zidane, no-one was questioning his sense of direction. Continue reading →

Argentina’s Rude Awakening at Italia ’90.

It was the opening game of the 1990 World Cup, with holders Argentina, including the mercurial Diego Maradona who had just almost single-handedly taken his Napoli team to the Scudetto, pitched against an African team representing Cameroon populated by players that hardly anyone had heard of drawn largely from the ranks of the lower tiers of French club football and similar less celebrated leagues. It was a chance for a rousing South American performance to set the wheels of the tournament spinning as they hit the ground. What happened however was of far greater significance. Continue reading →

When an ex-Blackpool goalkeeper got the better of Johann Cruyff, Franz Beckenbauer and Rodney Marsh – Vancouver Whitecaps and the 1979 NASL.

In the nascent years of football trying to force its way into the North American sporting consciousness with the North American Soccer League, there was a perceived need to bring in ‘big’ names from Europe or South America to give the game a fighting chance of gaining a foothold in an environment dominated by Basketball, Baseball and Grid Iron. Whether the plan worked or not is probably open to debate. The NASL folded in 1984, but perhaps the lid on the ketchup bottle had been loosened sufficiently for the later iteration, the MLS, to secure a more solid platform.

The NASL ran its race from 1968 to 1984 and star players, particularly those reaching the salad days of their careers were drawn into the league by the money being offered by a clutch of nouveau riche clubs, some backed by global organisations. Warner Brothers, for example, bankrolled the New York Cosmos, attracting the likes of Pelé, Franz Beckenbauer and Georgio Chanaglia amongst many others. Whilst the Cosmos were the richest club and built to dominate, others secured star names as well. Los Angeles Aztecs, part owned at the time by Elton John, secured the services of Johann Cruyff and George Best. The Washington Diplomats club was backed by the Madison Square Garden Corporation and as well as signing Johann Cruyff from the Aztecs, they brought in Wim Jansen, Cruyff’s team-mate from the 1974 World Cup Final.

Sometimes though, as Leicester City proved so wonderfully in 2016, big bucks and big names don’t always get the job done and in 1979, the eccentrically named ‘Soccer Bowl’ was won by a club some 20 miles north of the border between the USA and Canada, as a team managed by a former Blackpool goalkeeper and featuring no less than nine aged players from Britain, with varying degrees of celebrity, became the NASL top dogs. It was the year that the NASL doffed its cap to Vancouver. Continue reading →

Geoff Hurst – The stand-in who took Centre Stage

Some players go into major tournaments believing they are fated to play well, others settle for just expecting to play at all. For some however, there are tournaments where you’re selected as a squad player. The players in front of you seem well set in your position and there’s an inevitable dawning rationale that in all likelihood, you’re just there to make up the numbers. Most of the time, that’s just how it plays out. No-one remembers the players who never got on the pitch, and that seems to be your fate. Just occasionally though, the fates take a hand and the stand-in steps onto the stage to steal the show. In the 1966 World Cup, Geoff Hurst enjoyed such an experience. Continue reading →