World Cup 1950 Brazil: 2-1 Uruguay. The heart of Brazil stops

As James Rodriguez buried the second goal for Colombia there will have been an echoing of exhaling across Brazil from fans of the Selecao. This expression of relief more than joy would have had nothing to do with any solidarity amongst teams wearing yellow shirts. As the Colombians overcame a tepid Uruguay performance, any prospect of a repeat of the darkest day in Brazilian football’s history vanished. Brazil will now face the team fronted by Rodriguez, rather than the ghosts of their haunted past. Continue reading →

Cruyff in Oranje.

It’s often argued that for any footballer to be worthy of inclusion in the pantheon of the very greatest players of all time, as well as having success with their various clubs, they must also have excelled on the international stage, having accumulated appearances galore and delivered at the game’s most prestigious competitions. For example, Pelé made 92 appearances for the Seleção Canarinho, and played in four World Cups, winning three of them. Diego Maradona made one international appearance less than the legendary Brazilian star and also appeared in four World Cups, although only winning once, when he lifted the trophy as captain of La Albiceleste in 1986 after a dazzling individual performance. Franz Beckenbauer broke a century of appearances for the Die Mannschaft. He retired after playing 102 games for the national team. He only played in three World Cups, winning the tournament on home territory in 1974, but had also added a European Championship winner’s medal to his haul of honours, two years earlier.

With such standards to be measured against, the question arises as to how a player who appeared less than 50 times for his country – ranking at number 56 in the list of players with most appearances – played in just a single World Cup and the same number of European Championships, and never landed a single honour on the international stage, can be justifiably counted alongside the likes of Pele, Maradona and Beckenbauer as one of the true all-time greats of the game. The answer to that query is that the player in question is Hendrik Johannes Cruyff, more usually known as Johan Cruyff.

Whilst no one would contend that any of Pelé, Maradona or Beckenbauer were anything but generational talents, they each had the benefit of joining a team that had an established pedigree on the international stage. A teenage Pelé broke into the 1958 World Cup squad and, although Brazil were yet to win the trophy, runners-up in 1950 and a quarter-final appearance before losing out to the magnificent Hungarian team in 1954 illustrates that they were already among the top ranked teams in the world before he burst onto the scene. Further, after being injured in a group game in 1962, the Seleção went on to capture the trophy without him and have been crowned world champions twice more since he retired. Argentina won the World Cup without Maradona in 1978, and the Germans had won it once before Beckenbauer arrived in the team, and twice more after he had retired.

Such a pedigree of success was absent from the Dutch national team when Cruyff stepped onto the international stage on 7 September 1966. The Oranje had played in both 1934 and 1938 World Cups but had failed to win a single game, let alone progress in the tournaments. By the time they eventually made a return into football’s four-yearly jamboree in 1974, having been absent for 38 years, as David Winner states in Brilliant Orange, they had a World Cup record akin to that of Luxembourg. They had also failed to qualify for any European Champions up to that date.

In that game September 1966 game, another doomed qualifier for the 1968 European Championships, Cruyff’s debut for the Oranje was made alongside just two other players who would see action in the World Cup some eight years later. Ajax team-mate Piet Keizer appeared in just one game across the tournament, the goalless group game against Sweden, and Feyenoord skipper Rinus Israël who made a few appearances from the bench. Cruyff was hardly joining an established group of top players with a celebrated international pedigree. Yet, by the time he played his final game in Orange eight years later, the Dutch team had not only played in a World Cup Final and a European Champions and were on their way to a second successive World Cup Final, but had also been established as one of the greatest and most innovative international teams of all time. Equally, after his retirement from international football in October 1978, the Oranje would not attend a World Cup Finals for another dozen years. Typically, seven minutes after half-time in that debut against Hungary at Rotterdam’s Stadion de Kuip, he scored to put the Dutch two goals clear. Equally typically for the Oranje of the time however, two late goals from the visitors denied him a debut win.

The team was then managed by the German coach Georg Keßler who, surprisingly after the debut goal decided to drop the teenage Cruyff for the next game, a 2-1 defeat in a Friendly away to Austria. He was back however for the Friendly against Czechoslovakia in November of the same year. But, on 76 minutes, Cruyff became the first ever Dutchman to be sent off while playing for the Oranje. It led to a ban from the KNVB, which angered the already frustrated Cruyff. It wouldn’t be last time that he and the Dutch footballing authorities would cross swords. A goal on his debut and then a sending off in his second game, the scene was set for an international career that would be anything but mundane and ordinary – very much the reverse. Cruyff may not have been the only influence in such a dramatic rise in the fortunes of the Oranje but, in a 42-game career full of brilliance, bravado and bloody-mindedness in pretty much equal measure, as Brian Clough might have phrased it, he was in the top one.

Two years earlier, Cruyff had made his Ajax debut under Vic Buckingham with the English coach offering perhaps the greatest understatement of all time when he described the 17-year-old as ‘a useful kid’. It was under Rinus Michels however, who replaced Buckingham in 1965 that Cruyff’s football blossomed, with the new man at the helm quickly recognising the unique talent the club had and guiding him towards the full flowering of his abilities, before moving to Barcelona. Much as Cruyff’s influence grew with the Amsterdam club, as the years moved on and his insatiably demanding ability developed, the same would be the case with the Oranje, until the stage when he was widely considered to be a personality too large to be contained in a team environment.

The qualification campaign for the 1968 European Championships fell away, as so many others had done in the past and, when a 1-1 home draw against Bulgaria on 27 October 1969 with Cruyff absent once more, brought an end of Dutch hopes of a trip to Mexico the following year and World Cup qualification hopes were dashed once more, and Keßler’s time was all but done. The new man in charge was František Fadrhonc.

After a period of absence from the colours, the Czech-born coach selected Cruyff for a Friendly against Romania on 2 December 1970, and was rewarded with a brace from the returnee who was determined to state his case. Dutch hopes of qualifying for the 1972 European Championships were already in the Intensive Care Ward after a home draw to Yugoslavia and a defeat away to East Germany. In the next qualifier though, Cruyff bagged another brace in the six-goal romp against Luxembourg, before missing out again as qualification aspirations were all but extinguished by a defeat in Split’s Stadion pod Marjanom, when the absolute minimum of a draw was required to keep the faint hopes flickering. At the end of the group, the Dutch finished two points behind Yugoslavia, but the KNVB decided to keep faith with Fadrhonc for the campaign to reach the 1974 World Cup in neighbouring West Germany.

With Ajax now double European Cup winners and Cruyff the undisputed leader of the team and high priest of totaalvoetbal, he had also assumed the role of leading light in the national team. The qualifying programme began in May, and a 0-5 romp away to Greece, with another brace from Cruyff, set hopes rising, followed by success in a couple of Friendlies, a 3-0 win over Peru and 1-2 victory in Czechoslovakia with Cruyff opening the scoring. The qualifying group always looked likely to be a battle against Belgium for the sole qualifying spot, with the other members, Norway and Iceland, as the makeweights – and that’s how it turned out. When the two teams faced each other on 18 November 1973, they had each garnered maximum points against the group’s lesser lights, with a goalless draw in Belgium failing to offer either side much advantage. Belgium had scored 12 times without conceding, but the Dutch had doubled that figure and allowed their opponents as measly two strikes. It meant a draw was all that the Dutch needed to qualify for their first World cup in 36 years and, despite a massively controversial offside decision that ruled out a last-minute Belgian goal, they got that draw and headed across the border to West Germany.

With qualification sewn up, largely on the back of talismanic performances and seven goals across the six fixtures from Cruyff, the Ajax player was now the lead character and, accepted to be so by the KNVB who were allegedly acting under the player’s powerful influence when Fadrhonc was dismissed, despite being the first Oranje coach to get his team into the finals of a major tournament since the second World War. Cruyff’s old mentor Michels was temporarily seconded from Barcelona to take over. Before the tournament started however there were plenty more of Cruyff’s demands to be met.

Jan van Beveren had been the established first choice goalkeeper until a late season injury saw him miss the tail-end of the qualifiers with Piet Schrijvers stepping into his place. Van Beveren was one of Europe’s top stoppers and, when he regained fitness ahead of the tournament, a return to the national team looked inevitable, before a dispute with Michels saw him left out. Schrijvers looked to be the man to benefit but, reports suggest that with Cruyff pleading his case as supposed being more suitable to the creed of totaalvoetbal, Jan Jongbloed was the surprise selection between the sticks when the World Cup started. The 33-yearold FC Amsterdam goalkeeper had a mere five minutes of international experience behind him, as a late substitute a dozen yeas previously – and he had conceded in that briefest of spells. Nevertheless, with Cruyff as the driving force, the day was won and, in fairness the veteran did little to let anyone down, only conceding a single goal, and that a late own goal by Krol against Bulgaria with the game already won, before the Final when his limitations may well have been exposed.

Cruyff was also the main player in conflicts between the squad and KNVB over bonus payments and the decision to play in shirts provided by Adidas, carrying their famous three-stripe branding in black lines on the sleeves of the orange shirts. Cruyff was sponsored by Adidas’s arch-rivals Puma and refused to wear the design that had been agreed in contract by the KNVB. At first they stood firm and said the choice was theirs not the players. Cruyff countered by conceding that point but countered by asserting that the value was added by his head poking through the top of the shirt. Eventually peace was declared with a special two-striped version being provided for Cruyff. If there was any doubt who wax the first among what was surely a group of unequals, the squad numbering for the tournament told a telling tale. Numbers were allocated to the players on an alphabetical basis. The one exception being Cruyff, who was allowed to keep his number 14. For many of observers, so much of this may have looked like pandering to an inflated ego, and perhaps it was, but Cruyff’s performance in Germany justified all of that.

In the opening game against Uruguay, he pulled the strings of the Dutch attack with Johnny Rep scoring both goals that set the Oranje on their way. Four days later, the only stutter in the Dutch march towards the Final occurred when a determined, and well drilled, Sweden held them to a goalless draw. It was in this game however that Cruyff revealed the move that would carry his name for evermore. Cruyff had been drifting to the left flank of the Dutch attack on numerous occasions, allowing Rep to drift inside and seeking to unbalance the Sweden defence. When Rep played yet another wide ball to him midway through the first period, unbalanced was hardly a sufficient description for what was about to happen. Full-back Jan Olsson dutifully closed on Cruyff and, as he shaped to play the ball across field, the defender jabbed out a leg to intercept a pass that never came. Instead, Cruyff hooked the ball back between his own legs and scampered clear with Olsson looking as dumbfounded as a dupe in a conjurer’s trick. So far had he been sent the wrong way that he not only needed a ticket to get back into the stadium, he needed to hail a taxi to get back there first.

If the Sweden game had been grace, but not glory, that lack was remedied in the next game against with a comfortable 4-1 win over Bulgaria, that sent the Dutch into the second phase. The first game paired the Dutch with Argentina, and Cruyff scored twice in a 4-0 demolition of the South Americans that could been seven or eight goals had they been minded to press for them. His first goal was a mesmerising combination of athletic genius and balletic poise as he plucked a Van Hanegem pass from the air, danced around the goalkeeper and rolled the ball home. It was probably the most entrancing moment of the whole joyous Cruyff stellar performance in Germany.

A 2-0 win then eased the Dutch past East Germany and into a confrontation with Brazil Four years previously, the Seleção had produced magic of their own in winning the 1970 World Cup. This team carried the same name, but hardly the same ethics. In Germany they largely abandoned flair and style, deploying muscle and physicality rather than the grace of O Jogo Bonito. Beauty overcame the beast eventually though, and Cruyff’s goal that sealed the win on 65 minutes must surely have given him as much pleasure as any scored wearing his country’s orange shirt, albeit they wore white in that game.

And so, to the final. A game where Cruyff would be the leader of an orchestra that played sublime music, compelling the German to dance to their hypnotic tune. And yet, despite being a team of supreme talents, they lost their way and saw an early lead disappear. If anything summed up Dutch football with Cruyff, that was it. They entertained, entranced and enthused all lovers of the game, but their wings of wax melted as they flew too close to the sun. West Germany won the trophy, but Cruyff’s Oranje won the hearts of all football fans.

Michels left after the World Cup, to be replaced by the little known, and even less regarded coach George Knobel. It seemed a strange appointment to go from master coach to someone who had led MVV Maastrict, a md-table team, before taking over Ștefan Kovács’s all-conquering Ajax team. His tenure in Amsterdam would last just one season before being shown the door. It was a strange appointment and if anything, only increased the influence of Cruyff in the national team. Knobel was left as a hostage of fortune with the skills of Cruyff delivering success on the field, leaving the coach compelled to indulge his whims and wishes, or risk losing the team’s greatest asset.

The issue was perhaps best illustrated ahead of a European Championship qualifying game against Poland. By this time, Neeskens had joined Cruyff in Barcelona and the pair were granted dispensation to arrive late at training sessions due to the extra travel involved. The inch offered quickly got stretched to a mile though and, on one infamous occasion Cruyff arrived late after reportedly taking his wife shoe-shopping in Milan. As he and Neeskens arrived late for training ahead of the vital qualifier against the Poles, either Van Beveren or Willy van der Kuijlen, various accounts differ, was heard to remark “Here come the Kings of Spain.” Van Beveren and Van der Kuijlen were both PSV Eidhoven players and the number of PSV players in the squad and grown with the club’s success in the domestic game. That would do little to save them though. Whether Cruyff actually heard the remark, or it was related to him later is unclear. The upshot was however that he announced that Knobel had a choice. Either Van Beveren and Van der Kuijlen went, or he did. Unsurprisingly, Knobel bent the knee and the pair left the training camp. Other members of the PSV contingent, were initially prepared to walk out as well, but Van Beveren talked them out of it. Van der Kuijlen would later return to the fold, but the goalkeeper’s exile was much longer. Cruyff turned in a virtuoso performance. The Dutch won 3-0 and headed towards qualification. Would they have done so had Knobel backed Van Beveren and Willy van der Kuijlen and let Cruyff walk away instead? It’s one to ponder.

Sadly, the Oranje’s first venture into the truncated European Championship Finals was brief. Knobel was running out of time and respect within the squad. A row with Van Hanegem saw the Feyenoord player dropped to the bench and an ongoing dispute with the KNVB meant the semi-final against Czechoslovakia would be his last game. Cruyff was carrying an injury into the tournament and, on a wet and windy night, the Dutch lost both Neeskens and Van Hanegem to red cards and were eliminated in a sad and dispiriting performance. They went into the tournament as favourites, but such adulation ill fits with the Oranje and seldom heralds success.

There was little time for lament however. Knobel was shuffled away and the KNVB appointed Jan Zwartkruis in his place with qualifying for the 1978 World Cup under way in September. Placed in a group with Belgium, Northern Ireland and Iceland, the Dutch eased to qualification winning five of their six fixtures and drawing the other. At such times however, there is always room for unrest in the Dutch camp. Recognising the quality of Van Beveren, the new coach sought to reincorporate the goalkeeper into the squad with a sleight of hand, selecting him in the squad but not playing him in the hope that a renewed familiarity may encourage a reconciliation with Cruyff. It wasn’t to be. Frustrated by not being selected to play, Van Beveren eventually gave up the unequal struggle and officially retired from international football. He had made a scandalously low 32 appearances for the Oranje. Had merit been the sole criterion for selection, that number would surely have been doubled. Van Beveren missed out on the 1978 World Cup as, ironically, would Cruyff.

On 26 October, Cruyff featured in the 1-0 win over Belgium that completed the Oanje’s qualification programme. Few knew it at the time, but it would be his final game for the national team. Six weeks earlier, Cruyff had been sitting at home in Barcelona watching television when, what appeared to be a courier, appeared at his door. In reality, the identity of the visitor was somewhat different. Cruyff and his family had been targeted by a criminal gang seeking to kidnap Barcelona and the Netherlands star player. Fortunately, after Cruyff and his wife had been tied up, she managed to escape and raise the alarm. The culprits fled and the danger had passed. The trauma however would last much longer.

Leaving his family and travel to South America was too much a burden for Cruyff and he announced his retirement from international football. There were a number of campaigns seeking to persuade him to relent. Without revealing the true cause for his decision – he was advised by the Spanish police to keep silent about the whole affair, in case it encouraged others to repeat the attack – he was adamant. The international career of Johan Cruyff was over.

If one were to seeking to illustrate the influence of Cruyff on the national team, its fortunes before his arrival, the dramatic rise during his time in Oranje, and the decline afterwards, is evidence aplenty. Thirty-eight years absence from the World Cup were broken with two successive qualifications across a four-year spell, both of which were driven by the talismanic number 14. After 1978, the wait would stretch until 1990 before they returned. Pelé, Maradona, Beckenbauer won far more honours than Cruyff did during their international careers. Given that he won none, that would hardly be difficult. What none of that trio could say however is that arrived at a time when their teams were considered akin to the status of Luxembourg in international football terms and transformed them into, if not the best, then one of the international teams of all-time and surely the greatest never to have won a World Cup. How did that happen? It was because one of the greatest players, one with an insatiable desire to succeed and a self-belief that he could make it happen, first pulled on the Netherlands national shirt. For all of the arguments, disputes and dissent, it was a time of unheralded success. It was a time of magic. It was Cruyff in Oranje.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Cruyff’ magazine from These Football Times).

Nike – Swooshing into the early days.

In Greek mythology, the winged goddess Nike was the personification of victory in all fields, not merely athletic endeavours. It seems highly appropriate therefore that, when Blue Ribbon Sprots, a business formed by a handshake in January 1969, between an athletics coach and one of his former charges, was renamed in 1971, it chose that particular celestial appellation. Now one of the most iconic brands in the arena of sportswear, the Nike organisation has fully lived up to not only to the goddess’s virtuous reputation, but also to their own slogan – “Just Do It.” They just did.

The son of a former governor in Oregon, Bill Bowerman was born in Portland on the Pacific Northwest coast of the USA three years before the outbreak of World War One. Progressing through schools in Medford and Seattle, he completed his education at the University of Oregon, studying journalism and football. He then entered the world of work as a teacher at Portland’s Franklin High School in 1934, focusing on biology and, more significantly coaching the school’s football team. The latter would lead him to great success. Bowerman returned to his former school in Medford the following year, again taking up the role of coaching, and led his team to a state title.

As was the case for so many of his generation, the outbreak of World War Two brought an abrupt halt to his career. Bowerman served in the US Army until the end of the conflagration, before being honourably discharged in 1945. He resumed his career at Medford High School, before moving on to become head coach of the University of Oregon’s athletics team. Further success followed as the team blossomed under his tutelage, many using the foundations supplied by Bowerman to build into flourishing careers on the athletics track. One of the athletes benefitting from Bowerman’s coaching – or ‘teaching’ as Bowerman preferred to describe his methods – was Phil Knight.

Along with Bowerman, Knight was the other party of that famous handshake agreement in 1964. He had been an accounting student at the university and an aspiring middle-distance runner under Bowerman’s guidance. By the time he had shook hands on that deal however, he had graduated and, after a year in the army, enrolled at Stanford Graduate School of Business, before launching into a career in accountancy. He would later become a Professor of Accounting at Portland State University.

For an assignment in his Small Business Class, during his time at Stamford, Knight produced a paper portentously entitled “Can Japanese Sports Shoes Do to German Sports Shoes What Japanese Cameras Did to German Cameras?” He left Stanford in 1962 with a Master’s Degree in Business Administration, and then sought to find the answer to the question posed by his paper by visiting Kobe in Japan as part of a world tour.

The Onitsuka sportswear company, later to become Asics, was based in Kobe and, after being impressed by the quality and low cost of the running shoes they produced, Knight struck a deal with the company to sell their shoes in America. At first, the relationship seemed to be stuck in the mud, as the first samples of the Onitsuka Tiger brand shoes took a year to arrive with Knight back in America, where he began working as an accountant at Coopers & Lybrand, before later moving to Price Waterhouse.

When the samples arrived, one of Knight’s first moves was to send two pairs of the Tiger shoes to his old university coach Bill Bowerman, hoping for a sale and possibly even an endorsement. He received far more than that though. As well as buying both pairs of shoes, Bowerman suggested forming a partnership to sell the shoes and produce design suggestions.

A trip to New Zealand in 1962 had added fuel to Bowerman’s interest in running when he was introduced to the concept of using it as an aid to improved health and well-being, especially among older people. The idea took root and, when returning to America, he sought to develop the concept, writing articles for athletics magazines and published a three-page pamphlet titled “The Jogger’s Manual”. Three years later, partnering up with cardiologist WE Harris, Bowerman published “Jogging” a 90-page book that sold well over a million copies. The book is widely regarded as being the trigger that fired the starting gun on the American obsession with running for health and pleasure. Such was the book’s success, that the following year, a follow up – now grown to 127 pages – was published.

It was in this same period that Bowerman and Knight formed Blue Ribbon Sports. Knight would use his accounting and administration skills to run the business end of the enterprise based at the company’s office in Portland, while Bowerman, still working as a coach for the University of Oregon, would continue to experiment and develop his ideas of how to improve the design of running shoes.

Otis Davis, a double gold medal winner in the 1960 Olympic Games where he broke the world record for the 400 metres event, clocking 44.90 seconds and becoming the first man to dip under the 45 second barrier, was another of Bowerman’s athletes at Oregon. He insistently claimed to have been the first recipient of a pair of Bowerman’s custom designed running shoes, despite popular folklore suggesting it was Knight who first slipped his feet into a Bowerman creation. Davis tells the now legendary story of how Bowerman used his wife’s Waffle Grill to create the patterned soles of the shoes that would be lightweight, but also increase grip. He was, however, far less impressed with the outcome than millions of others would be with more traditionally created Bowerman inspired footwear of later decades. “I didn’t like the way they felt on my feet,” Davis recalled. “There was no support and they were too tight. But I saw Bowerman made them from the waffle iron, and they were mine.” The designs would improve.

To drive the business, Bowerman and Knight would visit various athletic meetings around the state, selling the Japanese shoes from the back of Knight’s green Plymouth Valiant car. Originally, a 50-50 partnership, Bowerman later insisted that agreement was amended to 51-49, in favour of Knight, to avoid the potential of any divergence of opinion stymying the company’s progress. Any new enterprise is always vulnerable to failure, but Blue Ribbon Sports enjoyed a successful first year in business selling more than 1,000 pairs of Onitsuka Tiger shoes, generating more than $8,000 in sales. The following year, that had grown to $20,000 and, in 1966, Blue Ribbon Sports opened their first retail outlet in Santa Monica, California. By 1969, Knight was able to wave goodbye to his accountancy work and devote his full attention to Blue Ribbon.

The business was growing but, merely being distributors for another company’s produce was never the long-term plan. Bowerman’s designs had graduated from leaving Otis Davis unfulfilled and utilising – and ultimately destroying – his wife’s Waffle Grill. In 1966, he produced a running shoe that was ultimately christened as the Nike Cortez. It sold well and, to this day, remains an iconic design in sports footwear. By 1971, Bowerman’s designed shoes were selling well. It was time for a change of direction for the business. Bowerman and Knight felt confident enough to launch a company solely based on their own produce and the partnership with Onitsuka was ended. A new company was about to be born and its first employee, Jeff Johnson, is credited with suggesting the name that it would carry on its journey to fame and great fortune. Nike was about to be born.

Two years earlier, Knight had met Carolyn Davidson during his time lecturing at PSU. The young Graphic Design student was struggling to find the funds to pursue a passion for oil painting. Knight agreed to offer her some freelance design work for Blue Ribbon Sports, at a reported rate of $2 per hour, producing charts and graphs for meetings with the company’s Japanese supplies. It was hardly felt like a life-changing engagement at the time, but Blue Ribbon was still a relatively young business and the money allowed Davidson to indulge her oil painting pursuits and, as the proverb suggests, “Mighty oaks from small acorns grow.”

Two year later, when Knight and Bowerman were looking to launch their new enterprise, Knight asked Davidson if she’d be interested in a project to produce a logo for them. Knight’s brief to the designer was hardly comprehensively packed out with detail, but that afforded Davidson a measure of creative freedom. He was looking for a something that would fit into the space available on the side of the shoe, suggestive of movement, or similar, and was identifiably different from the three-striped logo of Adidas. Davidson took on the task, and used sheets of tracing paper positioned across the side of a shoe to develop her ideas.

Legend has it that, given her other commitments, t Davidson was unsure precisely how long the project had taken her, and eventually charged it out at 17.50 hours, even though she was fully convinced that this was an underestimate. The fee for producing what would later become one of the world’s most recognised logos was invoiced out at precisely $35 – albeit a figure that, adjusted for inflation, would now be reaching towards $250.

For that sum, she produced a number of different options and visited the company’s office in Tigard, Oregon to present her concepts to a selection team comprising of Knight, and two fellow executives, Bob Woodell and the christener of Nike, Jeff Johnson. As in all good stories of this type, the initial reaction was hardly overwhelmingly enthusiastic. After rejecting the other concepts out of hand, the decision was made to go with what would become known as the Nike Swoosh, a concept Davidson had based on an adapted ‘tick’ with an echo of one of the wings from a statue of the Nike goddess. At the time of presenting to Knight and his colleagues, Davidson’s concept had the swoosh as an outlined shape, clear on the inside with ‘nike’ in lower case lettering overwriting it.

After the concept was selected, Davidson explained that the design was still in the raw state and requested more time to refine it to a final state, now that Knight and his team had made a decision. Knight however rejected the request, citing deadlines that had to be met and that the company would proceed with the design as it was. Feeling pressured by time, Knight felt the decision was necessary, if less than perfect. Somewhat less than enthusiastically, as stated on Nike’s own website, he confessed that, “I don’t love it, but it will grow on me.” It did. In 1972, the logo was carried on the side of Nike Cortez running shoe, and was registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in January 1974

Davidson continued to work for the new Nike business for a further four years, producing ads, posters and leaflets, whilst completing her studies and collecting a Batchelors Degree in design. After graduation and as the demands for work at Nike outgrew the capacity of a single designer, she left to work from home as a freelance designer, still unaware of how celebrated her $35 design project would become. The Nike corporate logo continued to carry the name of the company up until 1994, when the word, now set in all-capital Futura Bold font, was dropped, leaving the Swoosh to live on in splendid isolation.

The Nike Cortez was hardly the end of Bowerman’s development of sports footwear. He had an obsession about improving the efficiency of sporting shoes; one that would exact a tragic price in later life. With the target of reducing the weight of the shoe, and reducing drag from the design wherever possible, he could help the runner to increase speed, and energy efficiency. He calculated that, assuming the runner was six feet tall, removing just a single ounce from the weight of a running shoe would result in a reduction of 55 pounds in the effort of foot lift per mile run. Those thoughts drove his inspiration and innovation.

In 1972, he produced what came to be known as the ‘Moon Shoe’ due to its waffle inspired tread bearing a resemblance to the footprints left on the moon by astronauts’ steps. Two years later, the “Waffle Trainer” was launched, honouring Mrs Bowerman’s long- deceased kitchen gadget. It helped fuel the meteoric rise in Nike’s market share and continuing developments of the design go on to this day.

Sadly, there would be a price to pay for Bowerman’s diligence to the cause of sports shoe design. When experimenting with ideas, he would work in a small and poorly ventilated workshop, often using rubber compounds, glues and solvents containing toxic components. The long-term effect was to cause irreparable nerve damage resulting in severe mobility problems, and an inability to run, as the nerves in his legs were damaged. The sad irony of Bowerman eventually being unable to benefit from the shoes he designed was not lost in Kenny Moore’s book “Bowerman and the Men of Oregon.” In the late 1970s, surely guided by his diminishing health, Bowerman began to cut back his active involvement with Nike, but his legacy lives on with the company. Its headquarters are located in Bill Bowerman Drive and Nike have launched a range of high-performance running shoes labelled as the “Bowerman Series”. He passed away aged 88 and in declining health, in 1999.

In September 1983, three years after Nike had gone public, and a dozen since delivering the $35 design project for Knight, Carolyn Davidson was invited to a Nike company reception, where her erstwhile client presented her with a diamond ring made of gold, engraved with the Swoosh, and an envelope filled with 500 shares of Nike stock. The value of which has been reported to exceed $1,000,000 in contemporary values. The payment may have been a little late in coming, but it was delivered in full. Davidson later remarked upon Knight’s generosity, because she had “originally billed him and he paid that invoice.”

Phil Knight would continue to serve as CEO of Nike until November 18, 2004, a few months after the tragic death of his son Matthew’s funeral, following a heart attack whilst scuba diving in El Salvador, but retained the position of chairman of the board. He would relinquish that post in June 2016, a couple of months after publishing his memoirs in a book titled “Shoe Dog”. The following month, the book hit fifth spot on The New York Times Best Seller list. In 2021, Knight’s fortune was estimated at some $80 billion.

In 1988, Nike’s first ad using the slogan “Just Do It” was screened, after being pitched to the company by Dan Wieden of Wieden+Kennedy who had become Nike’s advertising agency after Carolyn Davidson had left. It featured an 80-year-old Californian named Walt Slack who spoke of how he took a 17-mile daily jog across the Golden Gate Bridge, and kept his teeth from chattering in the cold weather by leaving them in his locker at home. By this time Bowerman’s ill health had taken him away from the business, but the echoes of his promotion of running as an aid to health and well-being were clear.

There was also perhaps another, more subliminal reference to the early days of Bowerman and Knight’s partnership, and the early days of Blue Ribbon Sports. Anyone watching Knight and Bowerman driving around Oregon, hawking Japanese running shoes out of the back of a car at local athletics meetings, would consider it a long way from developing into a globally renowned organisation and accumulating such wealth. Sometimes however, you have to “Just Do It.”

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Nike’ magazine from These Football Times).

“Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe”

My seventh book – “Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe” – is published today.

Across the history of football, a select group of teams have achieved iconic status. Sometimes it’s through sheer success. For others, their stature is built by star performers. On occasions, it’s because a team has gifted a new way of playing to the world. Most rarely it’s because of all three. The Ajax teams that conquered Europe with their enthralling ‘totaalvoetbal’ are one of those rare cases. Those Dutch artists used the pitch as their canvas, the skills of the players provided a palette of gloriously bright colours and their totaalvoetbal inspired the brushstrokes that delivered masterpieces of football creativity. The Dutch Masters is the entrancing tale of how that iconic white shirt with a broad red band down its centre not only became synonymous with the beautiful game of totaalvoetbal, but also symbolised the success of the club that created a new paradigm of play. It’s the story of how Ajax came to dominate the European game as the epitome of footballing perfection.

Or visit my Amazon author page – amazon.com/author/gary_thacker – for full details of all of my books

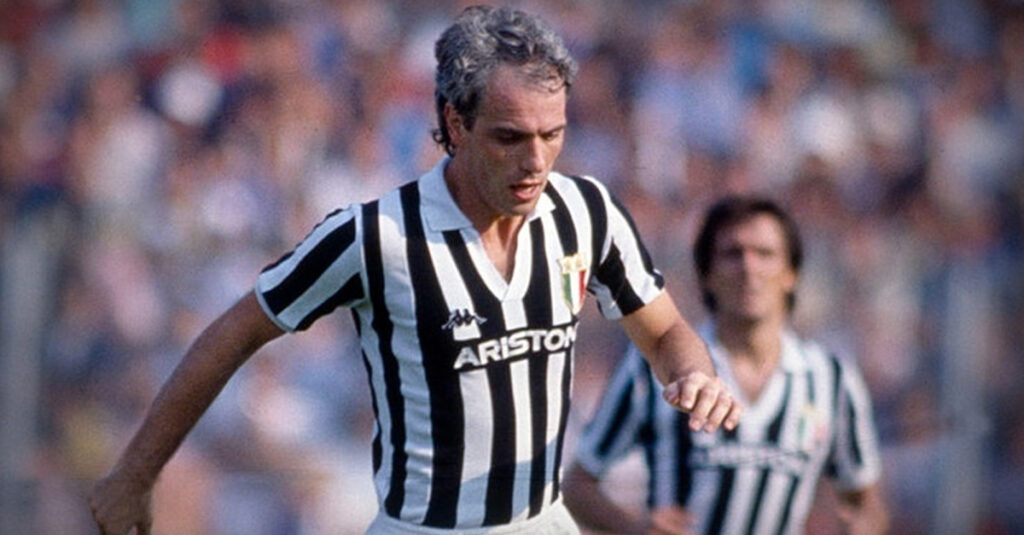

Roberto Bettega

It’s the strongest of all generational familial bonds; a mutual devotion built on the deepest of emotional attachment and respect, and one that applies nowhere more so than in Italy. The love between a mother and her favourite son endures eternally. It was the sort of bond established between La Vecchia Signora and Roberto Bettega, a child of Piedmont, born in Turin just after Christmas in 1950. For almost six decades Bettega devoted his career to I Bianconeri, first as player, and later as an administrator. Pumped by a heart of the same hue, white and black blood coursed through his veins. He even offered the Old Lady the gift of his son Alessandro, who joined the club’s youth system in 2006. Italian mommas love all of their children of course, but the ones who stay near and honour the gifts they have been given are the most treasured. That’s why there will always be a special place in the heart of La Vecchia Signora for Roberto Bettega.

The man who would become one of the most feared strikers in the history of Serie A originally fell into the embrace of the Old Lady as a young teenage midfielder in 1961, when he was accepted into the Primavera squad at the Stadio Comunale. By the beginning of the 1968-69 season, he had progressed to the first team squad. Initially elated to have reached such an exalted position whilst still in his teenage years, that joy slowly turned into frustration, granted a mere watching brief as the season ran its course without him recording his debut.

The season also brought frustration to the club, and the Juve tifosi. A fifth place Serie A finish, no less than ten points astray of champions Fiorentina, was not the standard required and the five-year reign of Paraguayan coach Heriberto Herrera was brought to an end. By now converted into a forward, Bettega was anxious to prove his with to the club and hoped the arrival of the new regime would change his fortunes. It did, but hardly in the say he had hoped. The new man in charge, Argentine Luis Carniglia, decided that there was little chance of Bettega making any meaningful contribution to the first team in the coming season, and he was sent out on loan to nearby Serie B club, Varese.

It was the sort of disappointment that could crush the spirit of an aspiring player who wanted little else than to wear the white and black stripes of his beloved Juventus. Fortunately, Bettega was made of sterner stuff and, during his time at the Stadio Franco Ossola, had the unexpected benefit of falling under the coaching of Nils Liedholm, the Swedish forward, who had enjoyed such a stellar career with AC Milan in the fifties and early sixties.

It’s difficult to discern how much Liedholm contributed to Bettega’s development, but a record of 13 goals in 30 league appearances – making him the Serie B top goalscorer – was enough to convince the Swede that here was a rare talent, about to blossom into the full flowering of an outstanding career. Knowing more than a little about what makes a great striker, Liedholm enthused about Bettega’s potential. “He is particularly strong in the air, and can kick the ball with either foot,” he commented. “All he needs is to build up experience, and then he will certainly be a force to be reckoned with.” Varese won promotion on the back of Bettega’s goals and Liedholm’s coaching. Each would later leave and go on to further, and greater, successes. Liedholm moved on Fiorentina at the end of the following season, and Bettega returned to Juventus. His CV had been stamped by Liedholm and he was ready to stake a claim for a place in the Juventus team. The timing could hardly have been better for both parties.

Whilst Bettega had been plundering goals for Varese, Juve had struggled under Carniglia and, before the end of the season, he was replaced on a temporary basis by Ercole Rabitti, with a remit to steady the ship before a new appointment at the end of the season. Rabitti stabilised the club guiding them to fifth place and qualification for the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. It was a recovery of sorts, but hardly sufficient to suggest a longer tenure, and Juve turned to Armando Picchi, the former Libero of Helenio Herrera’s all conquering ‘Grande Inter’ team. It seemed like an ideal appointment, but tragedy would deal a cruel fate for the 36-year-old who had previously coached the Azzurri. He wouldn’t see out the season. In February 1971, Picchi was diagnosed with cancer. Three months later, after a brief period in hospital had ended his coaching career, he passed away.

Bettega had made his long-awaited debut in September of 1970. His chance came in the away game against Catania and the young forward announced his arrival by scoring the winning goal. Despite that goal being his only strike before the turn of the year, it heralded more than a decade of goals that would follow in time. It wouldn’t be the last time that Roberto Bettega would please La Vecchia Signora by delivering such presents.

On 17 January, he returned to the scoresheet scoring the opening goal in a 2-1 home victory over Foggia. The elation of his first Serie A goal at the Stadio Comunale may have been just the spark to ignite Bettega. A single goal from the start of the season to the end of 1970, was followed by a dozen more before the end of the season. Following his debut goal against Catania, Bettega had waited four months to notch his second goal. After securing it against Foggia, the wait for number three was much shorter. The following week, he again scored Juve’s opening goal as I Bianconeri overcame Fiorentina 1-2 in the Stadio Artemio Franchi. The dam had well and truly been breached and on the final day of January, back at home in Turin, Bettega recorded the first hat-trick of his career in the return fixture against Catania, as Juve cantered to a 5-0 success.

The tragic fate of Picchi would, of course, cause a major problem at the club, but with Czech coach Čestmír Vycpálek promoted from the youth team to guide the club until the end of the season, a further six goals for Bettega helped the club to record a highly respectable fourth place. Bettega ended his debut season as a first team player with 13 goals and the proud record of Juve never having been beaten when he had found the back of the net.

While Rabitti’s brief tenure at the club had been insufficient to convince the club’s hierarchy that he was worthy of a permanent position, that wouldn’t be the case with Vycpálek. His ability to inspire, particularly with the younger players, whom he had worked with in his role with the youth team, held out the promise of success to come, with the goals of Bettega being a prime example. Vycpálek was given the permanent position as the club and Bettega looked forward to an exciting season to come.

Initially, the stars seemed to be perfectly aligned for Juve and, particularly for Bettega. With confidence topped up from his end of season form, an astonishing run of ten goals in his first 14 games of the new season announced to Serie A, and the wider footballing world, that the Old Lady had brought forth another outlandishly talented son. The dream start to the season would turn into a nightmare though. Early in the new year, with Juventus flying high, Bettega netted against Fiorentina. It would be his last goal until September of the same year, as ill health once again cast a dark shadow over the Stadio Comunale. This time it was their free-scoring tyro forward who fell into its malicious grasp, when a lung infection that at times threatened to turn into tuberculosis, brought his season to an end. The impetus given by Bettega’s prolific opening to the season however was sufficient to see Juve secure the Scudetto, by a single point from AC Milan.

It was a bittersweet moment for Bettega. Still only 21, the young forward had ignited the club’s revival and their first Serie A title for five years, but illness had deprived him of the joy of taking a full part in the jubilation. If he felt that fate had been less than generous to him on that occasion though, he would receive full recompense across the coming years as Juventus launched into a golden era of success and silverware, driven by the goals of Roberto Bettega, but a little patience would be asked of him first in way of payment for the glory to follow.

The champions of Italy opened the defence of their crown on 24 September 1972 with a 0-2 victory away to Bologna, and Bettega making his return to first-team action, following long months of recuperation. The result was an ideal start to the season for the club, as Franco Causio and Pietro Anastasi netted the goals. For Bettega though, although now free of the infection, the debilitating long-term effects of the illness were becoming clear, and would blight his season.

Juve would go on to retain the Scudetto by a single point from AC Milan, but it would be the goals of Causio and Anastasi – who would end the season as joint top scorers – as the prime driving force for the club. Bettega would end with just eight league goals. Juve also reached the final of the European Cup, before a timid display saw them lose to reigning champions Ajax. Bettega would start the game but be substituted at the break. Not being able to fully contribute in that game, must have felt like a microcosm of Bettega’s season.

The following season also brought frustration. Juve’s success at winning, and then retaining, the league title had made them prime targets for aspiring rivals. Vycpálek’s magic was beginning to wane and, as he chopped and changed his team in search of an elusive successful formula, Bettega’s game time was reduced. A decline in goals was an inevitable corollary. He would feature in just 24 league games, scoring eight times as the Scudetto was lost to Lazio. Vycpálek left at the end of the season, and replaced by Carlo Parola.

Parola was also a son of Turin and had appeared in more than 350 games for I Bianconeri as a redoubtable defender, very much in the style of the Italian caricature. He had won two Serie A titles, plus a Coppa Italia, and starred as the club’s captain from 1949 until leaving for a brief spell with Lazio as his playing career drew towards a close. He had also served briefly as coach on a couple of occasions a dozen or so years previously. His return would also see the league title back in Turin as Juve topped the table, two points clear of Napoli.

Once more though, whilst the club enjoyed success, Bettega’s star shone less brightly than some others. Ten goals in 47 games across all competitions was a poor return for an avowed goalscorer, but also emphasised his value to the team, even when he wasn’t finding the back of the net. It seemed that when he delivered prolific goalscoring seasons, the club would falter and, at other times, the reverse would apply. As if to illustrate that frustrating truism, as Juve lost out in the chase for the title to city rivals Torino, the following season, Bettega delivered the best goalscoring return of his career to date, scoring 18 goals in 36 games across all competitions and a highly impressive 15 in 29 Serie A games. A ratio of better than a goal in every other game in a league where excellence in defence was highly prized and almost revered as an art form was a rare achievement. Parola would leave at the end of the season.

After ascending to the first team squad in 1969, Bettega’s time as a Juventus player had seen no less than six different coaches take charge at the club. Heriberto Herrera was in place as he arrived. Luis Carniglia, and then Ercole Rabitti in the 1969-70 season. The tragic Armando Picchi had begun the 1970–1971 season before Čestmír Vycpálek took over and then Carlo Parola was appointed. Ideally, for Roberto Bettega, the next man in line would provide the elusive answer to combining seasons where both the club won silverware and the forward scored copious amounts of goals.

Giovanni Trapattoni would not only stay in post for the remainder of Bettega’s time with the club, but would also square that elusive circle of combining club success with prolific seasons for Bettega. In his first season, Juventus regained the Scudetto from Torino by a single point despite largely being a team in transition, and Bettega bettered his haul from the previous season, delivering the best goals return of his entire career.

Anastasi had now left the club and was replaced by Roberto Boninsegna. The newcomer’s partnership with Bettega would provide fearsome firepower for Juventus as they notched a combined 43 goals across all competitions. Bettega was the senior partner with 23, and Boninsegna adding 20. Just how influential the pair were is emphasised by the next highest scorers, Franco Causio and Marco Tardelli, only scoring seven each. Juve had begun like a runaway train, winning their first seven games and, in November showed that they had a steel to their game as well, recovering from two goals down in the San Siro to beat AC Milan 2-3. Bettega would net two of those three goals to lead the fightback.

Another test arrived the following month when, as nominally the away team, Torino halted Juve’s 100% record with a 2-0 in the Stadio Comunale. It put a stumble into Juve’s march but, with Bettega delivering goals aplenty they picked up the pace with the decisive game coming in April when, once again Bettega opened the scoring in a 2-1 win over Napoli. The result meant that, with three games to play, unless Juve slipped up, Torino wouldn’t be able to overhaul them. A 2-0 win away win to Inter was secured and with Bettega scoring in the next two games, the winning strike against Roma at home and then another in the game away to Sampdoria, the title was secured with Bettega’s goals being the key factor. It was a similar case in the UEFA Cup, where Juve had qualified courtesy of their runners-up position the previous season.

Juventus had disposed of both Manchester clubs in the first two rounds, but Bettega had failed to score in any of the four games. That would change in the third round though as he notched the lead-off goal in a 3-0 home win over Shakhtar Donetsk in the first leg. A 1-0 defeat in Ukraine eased Juve into the Quarter-Finals and a comfortable passage against East Germany’s Magdeburg. If anything, the Semi-Final victory against AEK Athens was even less taxing. A Bettega brace in the home leg as part of a 4-1 win had, effectively, settled matters before the return in Greece, but another goal from Juve’s main man brought a 0-1 win to confirm progress the final where Juve would face Spain’s Athletic Club. A narrow 1-0 win in Turin left things in the balance but, when Bettega scored early in the return game in Bilbao, it proved to be the decisive goal. His strikes were not only for the statisticians now, they were delivering trophies, and a total of 23 goals in 46 goals across all competitions was compelling.

When the new season opened with a 6-0 hammering of Foggia, the writing was already on the wall for Serie A. The title was retained by a more than comfortable five points. The Scudetto stayed in Turin and in the World Cup during the summer of 1978, the success of Juve was illustrated when no less than nine of the team starting against Hungary for the Azzurri were Juventus players. Bettega, of course, was one of them, and he scored.

In the following couple of seasons, the powerbase in Italian football seemed to have drifted from Turin to Milan. In 1978-79, the title went to the Rossoneri, with Juventus in third place, trailing by seven points. Success in the Coppa Italia was scant compensation given Juve’s previously dominant position. The Scudetto was then passed to fellow inhabitants of the San Siro as Inter took top spot, with Juventus three points behind in second place. Things would improve though, as Bettega continued to find the back of the net, scoring eleven and then 17 goals in each of those two seasons. The latter saw him securing the Capocannoniere award as Serie A’s top goalscorer. It seems strange that, given his consistent success over the years, that this was the first, and only, time ne would achieve that distinction.

Juventus had now gone two years without a league title and their shirts were looking a little bare without the shield that they had become do used to adorning the white and black stripes. That situation would be rectified in the 1980-81 season though, as once more Trapattoni guided I Bianconeri to the title. Injuries caused Bettega to miss a number of games, but he still contributed goals to the cause. Now moving into his thirties, the forward was compelled to adapt his style to the more cerebral and perhaps less dynamic play that age and experience both demanded and allowed.

The following season would see Juve retain the tile, but there was tragedy ahead for their star striker. Entering the European Cup, thanks to their title success the previous season, both Juve and Bettega held high hopes of continental success. The inevitable Bettega goal in a fairly comfortable passage against Celtic did little to persuade otherwise but, during the game against Anderlecht in the next round, a collision with the Belgian club’s goalkeeper was the beginning of the end of Bettega’s career with his beloved Juventus. A traumatic knee injury, with ligament damage would not only severely curtail his abilities, but also rule him out of contention for the 1982 World Cup, where fate again turned its face against him as the Azzurri won the tournament. Before the game against Anderlecht, Bettega had demonstrated that there were still goals aplenty to come. Five strikes in seven Serie A games and eight in 14 games across all competitions had put him bang on course for another prolific season. It was a level of performance that suggested he would smash his previous best goal-scoring season back in 1976-77. He would be robbed of the opportunity to deliver on that promise.

Any such injury during a player’s career can be catastrophic. By the time fitness had been regained, Roberto Bettega was 32 years old. At that age, the damage was terminal for a career built on an athleticism and technical ability now diminished by injury. It was as kryptonite to Superman. The 1982-83 season would be his last for the club. A return of just six goals from 27 games, contrasting with five from the opening seven in the previous season, bore testament to the physical damage sustained.

At the end of the season, it was clear to Bettega that his career at the top level of football was over. It was time to, at least temporarily, cut the emotional apron strings that had tied him to La Vecchia Signora. Across 13 seasons with Juventus, he made almost 500 appearances for I Bianconeri, delivering 178 goals, seven Scudetti, a Coppa Italia and a UEFA Cup. He would move to Canada and play out the dying embers of his career with Toronto Blizzard.

With his boots hung up, there would be a last return to Juventus as his old club called on Roberto Bettaga’s services once more; albeit in an entirely different sphere of activity. In 1994, club chairman, Umberto Agnelli, invited him to return to the club as vice-chairman. It was a call he willingly accepted and stayed in the role for a dozen years, sharing in more success at the club, and returning to pick up the position again for a year in 2009, before new chairman, Andrea Agnelli took control. His job had been done, family obligations completed.

There’s a special place in fans’ hearts for a one-club player and, despite brief sojourns to Varese and Canada, that was surely what Roberto Bettega was. Not only had he been one of the club’s top scorers off all time, his devotion and loyalty to the club also meant he was one of the most loved by the tifosi. There’s surely only one accolade higher and that’s to laud Roberto Bettega as a loyal and loving son to his Momma, La Vecchia Signora, the Old Lady of Turin.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Juventus’ magazine from These Football Times.

Didier Drogba

So many top echelon footballers of the modern era are, or were, graduates of academies run by the richest clubs who scoop up any promising talent and ‘hot house’ them to produce the most precious and rare of blooms, whilst the vast majority of others are cast aside, discarded like so many weeds. For so many of the successful minority, it means that the ‘rites of passage’ enjoyed and even often endured by the mere mortals who watch them and pay homage to their brilliance are absent from their development as both footballers, and more importantly, people. Sadly, but to the delight of certain sectors of the media, this can lead to poor life decisions and the type of errant behaviour that offers easy headlines for the red top newspapers who seem so anxious to feast on the fates of supposedly fallen angels, screaming about too much money, too young and not enough common sense. No one ever prints an article about a player headlined ‘Footballer Goes Home and Does Good Things.’

Some players however, have earned their celebrity, fame and fortune by walking much less comfortable paths, enduring a nomadic lifestyle in pursuit of their dreams, travelling to different clubs, often having their resolve tested by injury and rejection of both professional and societal variations. Sometimes this is a factor of the location of birth, sometimes it’s caused by the scarcity of life chances, sometimes by a lack of belief, often by a combination of many such factors. Those who make their way to the top by these less-travelled roads though have learned life’s tough lessons, qualified from the school of hard knocks and graduated from the university of life. The journey was more difficult, but their personal development so much more complete.

Didier Drogba was born on 11 March 1978 in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire to a fairly comfortably off family. Seeking to offer their son the best opportunities that life could offer away from Africa, the five-year-old Drogba was packed away to France to live with his uncle and aunt. It was a traumatic time for the young boy, who yearned for the comforting normality of his home back in Africa, where he didn’t feel so ‘different’ as he described his time in France. While his surrogate parents were both loving and protective, it was an understandably difficult period, and three years later he returned to Cote d’Ivoire. Unfortunately, despite the welcome return to the verdant surroundings of his homeland and his love of Cote d’Ivoire that was burnt deep into his soul – just how deep would be illustrated much later in his life – he was again compelled to leave Africa and rejoin his uncle in 1991, when both his parents lost their jobs as recession gripped the African country. Two years later, together with his siblings, they would join him in his new French domicile.

Despite the struggles and strains of growing up in a foreign country, Drogba’s determination to play football professionally had been hardened by the early life experiences that had taught him the value of family and belonging. They would also guide him through life. Despite hardships and rejection by some clubs, he eventually achieved a breakthrough into the professional ranks at Le Mans. He was 21 years old. By this age, most players who go on to establish themselves at the highest levels were already several rungs ahead of him on the climb to success. For Drogba, he had only just found the ladder. From there he moved on first to Guingamp, before finally alerting the football world to his talents at Marseille.

The biggest break of his career came in July 2004, when José Mourinho, newly installed as Chelsea manager, and making hay with the largesse of Roman Abramovich took him to Chelsea in exchange for £24 million. The following eight seasons, and the success enjoyed by Chelsea, would raise Drogba’s celebrity from merely that of a footballer to an iconic figure in the British game and across the continent. Scoring 157 goals in 347 games for the Stamford Bridge club, Drogba would collect three Premier League titles, four FA Cups, two League Cups, as well as host of personal awards. His time with the club was by netting the winning strike in the penalty shootout that made Chelsea Champions of Europe for the first time in 2012, beating Bayern Munich in their own stadium with the final kick as a Chelsea player before moving on as his contract expired. After periods playing in China and Turkey, he would return to West London two years later and add to his trophy haul by winning another league title and a third League Cup.

Speak to any Chelsea fan and they’ll regale you with golden memories of Drogba’s time at Stamford Bridge. ‘Drogba Legend’ reads one banner in Cote d’Ivoire orange, strung across the stand at the ground where he delighted so many fans. Even for fans whose adherence may be to a different club, there’s often a grudging admiration and a nod of acceptance for a player who defined the role of the lone front man in Premier League football. For a player who had reached the peak of the game through a dogged determination and no little ability, that success may be enough of a story. It is, however, a long way short of defining who the ‘real’ Didier Drogba is.

While he was away from the country of his birth, Cote d’Ivoire suffered the fratricidal horrors of a civil war. The Muslim-dominated north sought to break away from the mainly Christian south of the country as religiously fuelled internecine conflict raged. When prosperity turns to poverty as global economic tides wash away security and peace of mind, divisions that were once less important, suddenly assume new prominence and inspire frenzied devotion. The conflict that began in 2002 had by 2004 settled into a struggle where neither party was capable of subduing the other and the country suffered an uneasy stalemate, punctuated by far too regular bouts of fighting and bloody conflicts. Attempts at peacekeeping by France and the UN were well-intentioned but doomed to fail as antagonisms became more and more engrained. Only one thing united all Ivorians, the national football team, The Elephants, led by Didier Drogba.

For the iconic leader of the team, it was an opportunity to try an offer a balm to the open wounds of his country. In the qualifying tournament for the 1996 World Cup, after each game, Drogba would gather his team-mates around him, and lead them in prayer for peace in their homeland. It was heartfelt and, for a man like Drogba with that love of his country pulling at his heartstrings, it was important, but a bigger, more significant step was required.

On 8 October 2005, Cote d’Ivoire travelled to Sudan to complete the qualifying programme, a win would take them to the finals. Akale scored in the first half and a brace from Dindane after the break sealed the win, despite a late goal for the home team. The game was a triumph for The Elephants, but what followed was even more important for the future Cote d’Ivoire.

As pictures of the Ivorian dressing room wildly celebrating qualification for their first World Cup Finals were beamed back to the country by Radio Télévision Ivoirienne, amid the joyous scenes, Drogba asked for the reporter’s microphone, calling for silence. At that moment, in the suddenly eerie quiet of the small dressing-room at the El Meriekh Stadium in the Sudanese city of Omdurman, Didier Drogba moved from being merely a highly paid professional footballer into a humble but hugely influential national hero.

In humble but determined tones, he addressed the whole of Cote d’Ivoire. ‘My fellow Ivorians, from the north and from the south, from the centre and from the west, we have proved to you today that Cote d’Ivoire can cohabit and play together with the same objective: to qualify for the World Cup. We had promised you that this would unite the population. We ask you now.’ He paused as he sank to his knees in supplication to the watching millions of his countrymen. ‘The only country in Africa that has all these riches cannot sink into a war this way. Please, lay down your arms. Organise elections. And everything will turn out for the best.’ He paused, bowing his head then, looking into the camera spoke again. ‘Forgive,’ he begged.

In his autobiography, Drogba confessed that he had no idea how his plea would be received. All he knew was that ‘it had come from my heart and was completely instinctive. It came from the love I had for my country and my sorrow at the state it was in.’ When he arrived back in Abidjan however, the full effect of his heartfelt message became clear. It had been a cathartic moment for the country. Suddenly, inspired by a mere footballer, hope for peace was renewed. His words were replayed over and over again and tensions began to ease. When later interviewed on national television and asked for his emotions, Drogba was clearly speaking from the heart. ‘I have won many trophies in my time,” he declared, “but nothing will ever top helping win the battle for peace in my country. I am so proud because today in Cote d’Ivoire, we do not need a piece of silverware to celebrate.’ What the UN and France had failed to achieve had been delivered by Didier Drogba. It was far from being the end of the conflict, but it was a significant step on the road to it and Drogba wasn’t going to stop there.

Tensions had eased, but it remained an uneasy time, and a stubborn impasse between the north and south of the country still dogged efforts at reconciliation. More action was required. Two years after his speech in Sudan, a qualifying game for the Africa Cup of Nations was due to be played in June 2007 in Abidjan, but Drogba had other ideas. Using his newfound celebrity that had now allowed him access to people of influence, he approached the south-based government with a startling suggestion. Instead of staging the game in Abidjan, it should instead be moved 300 kilometres north and played in the rebel stronghold of Bouake. It would, he argued be a major gesture of reconciliation. To comply required a major shift of government policy but, such was the prestige achieved by Drogba, they felt compelled to agree.

On 3 June 2007, Cote d’Ivoire beat Madagascar 5-0 in Bouake. It’s a short sentence that details the result of the game, but says so little about its significance. The rebel leader Soro Gauillaume had agreed a peace accord with President Laurent Gbagbo, and sat beside him at the game. Around 300 rebel soldiers also sat in the stadium alongside another 200 from the south who had, and officially still were, sworn enemies. There was a danger that placing previously implacable enemies in close proximity was akin to a lit powder keg and yet, despite the passionate support for The Elephants, there was also an air of tranquillity. The game, and its switch of location, had been an outstanding success. A spokesman from the Ministry of Sport declared that Drogba and his teammates had done more to bring about peace in the country than any politician, any international force, or any internal powers. The newspapers agreed, with headlines praising The Elephants and, of course, Drogba. ‘Five goals to Erase Five Years of War’, they read. ‘Drogba brings Bouake back to life’ and ‘Drogba magic.’

Elections duly followed in 2010 but, perhaps as was inevitable, accusations of malpractice and rigging dogged the outcome, and the conflict flared to life again. The solution would still be a distance away, but the journey towards peace and an end to the civil war had begun. In 2015, the country elected Alassane Ouattara as the president of Cote d’Ivoire by an overwhelming majority. The new leader of the country announced that, echoing a similar move in South Africa, a Truth, Reconciliation and Dialogue Commission would be set up, tasked with resolving remaining disputes and forging a new national identity for the country. It would compromise former ministers, religious and regional leaders, plus one other, a footballer. He gave it the extra legitimacy required to be accepted by all Ivorians regardless of religious or political affiliation.

In 2007 Drogba had announced the creation of a foundation bearing his name to help with education and health in Cote’ d’Ivoire, with particular regard to children. As well as supporting it from his own finances – as he describes in his autobiography, since its inauguration, ‘I made the decision to donate all my commercial earnings to the foundation, and I have continued to do so ever since’ – he also uses his celebrity status to encourage other contributions as well. Drogba has said that, “There is nothing better than when you see a kid with a smile on his face and that is why I’m trying to help. I want to do a lot of things in Africa, I want to give people the chance to dream, and it is easier to dream when you are in good health and happy.” His work continues.

With echoes of the former footballer – and fellow former Chelsea striker – George Weah being elected as president of Liberia as the model, Drogba has been encouraged to stand for election as president of Cote d’Ivoire. Were he to do so, he would surely be a strong candidate to lead the country, with popular support assured. Despite such promptings though, he has refused. The work he has done in his homeland has been made possible by his identity as a non-partisan force, seeking to unite his people without fear or favour to one group or another. Adopting a political stance, with inevitable conflicts arising from policies would surely dilute this. Drogba has been astute enough to distance himself from any party’s approach.

To many football fans around the world, the story of Didier Drogba speaks of the muscular front man wearing Chelsea blue and, often as not – a relic from his early days in the Premier League – an opportunistic ‘diver’ throwing himself to the ground in order to win free-kicks or penalties, and a theatrical exponent of the over-emphasised injury. To others he’s the archetypal striker that all clubs would cherish. Whilst some of those aspects have validity, they are so very far from the full story. Didier Drogba is a man who didn’t fall down easily at the most important moments of his life. Instead, he stood up to be counted, and used his celebrity and wealth for the benefit of so many others in his homeland. That potential headline of ‘Footballer Goes Home and Does Good Things’ could never be more apposite than if it were telling the story of Didier Drogba.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘African Forwards’ magazine from These Football Times).

‘We knew then. We know now.’ – The rise, fall and rebirth of Adidas.

The slogan in the title was coined for an advertising campaign mounted by Adidas ahead of the Atlanta Olympics of 1996. It was created to emphasise how the company’s relationship with Jesse Owens ahead of the Berlin Olympics had been a key factor in the American athlete’s success and that, remaining true to their principles, 60 years later their relationship with Donovan Bailey also helped him to 100 metres gold. What they knew then, they know now. What worked then, works now.

Those same words however, could also serve as the template for how the company was resurrected to its former glories in 1993 after a period of decline. Following the turmoil and decline of the Tapie years, the organisation’s new owner, Robert Louis-Dreyfus, as well as introducing innovative processes, returned to the established practise of creative marketing and developing relationships with individual athletes and organisations that led to its revival and drive back to the top table of the sportwear businesses.

Famously, Adidas had been formed by Adolf ‘Adi’ Dassler – the company name being an amalgam of the first three letters of his abbreviated Christian name and surname – back in 1947 after a split with his brother Rudolf, who went on to found rial company Puma. For the next decades, each brother sought to outperform their sibling as their businesses battled for supremacy in the sportswear industry. Adidas prospered from their founder’s innovative attitude to the design of sports shoes and the relationships and endorsements that he obtained from athletes for wearing them. It was an approach that would continue to pay huge dividends for Adidas over the coming decades.

When Adi Dassler passed away in 1978, his wife Käthe had taken the helm of the business and their son, Horst Dassler became part of the organisation’s top management. Three years later, when Käthe died, it was Horst Dassler who assumed control of the business. An inveterate marketeer, although still only his mid-forties, Dassler quickly identified the paths the company would need to follow in order to prosper. As well as newcomers to the market – such as the American company Nike whose slick marketing had led to them trebling Adidas’s market share in the USA – Puma, his uncle Rudolf’s company, had shown the way forward by pushing into the consumer market for athletic footwear and increased its sales in that field by 35% in the year before Horst Dassler took control. It was a market that Adidas had largely missed out on, but one that the new company chairman saw great opportunity in.

The new man in charge wasted little time in putting his ideas into practise. He sought to modernise the business and inserted an experienced professional management team to deliver the plan he regarded as essential for the company’s success. Inevitably, it meant a lessening of the influence of family members in the business, a trend that would intensify after his death. With the new regime in place, and with an echo of his father’s initial strategy, Horst Dassler’s Adidas focused on developing long-term relationships with both sporting bodies and the top individual athletes in a range of sports across the globe, using their successes and high-profile images to position Adidas, and their products, as the essential partner for sporting success.

These links were then used to feed marketing into the burgeoning ‘leisure’ sector and make Adidas the sports goods of choice for any aspiring sportsman, whatever their level of ambition. It was an astute piece of marketing, and one that brought major success for the company. By the time of his death on 9 April 1987, Horst Dassler had made Adidas, the world’s largest sporting goods manufacturer, with affiliated organisations in more than 40 different countries across the globe.

In 1989, Adidas became a stock corporation, and the following year, Horst’s children, Suzanne and Adi, disposed of their shares, cashing in on the success of their father’s enterprise and the break from the Dassler family was largely completed, although the strategies of both Adi and Horst Dassler would be revived further down the road. If that break benefitted the heirs of the business’s founder and his son financially, for Adidas, the loss of Horst Dassler and the consequent sale of the business would bring a change of ownership, a dramatic refocusing on strategy, and troubled times both with regard to image and financial stability, leading to record losses by 1992.

Bernard Tapie was a hugely controversial character in French business circles who had accumulated a fortune across the previous two decades by buying seemingly bankrupt businesses, turning them round, and then selling on for a large profit. To some he was considered the epitome of entrepreneurism, the embodiment of the ‘greed is good’ culture, not quite the Gordon Gekko of the ‘Wall Street’ movie of 1987 fame, but many saw the link. To others his business practises lurched towards the parasitic, a perception that the scandals, trials and tribulations of his later life only added supporting evidence to. In 1992, backed by a raft of substantial loans secured through a number of foreign financial institutions, plus part of the French Crédit Lyonnais bank, he raised almost 1.6bliion francs to purchase the shares of Adidas. The company had a new owner. Tapie had large shoes, sporting shoes, to fill. The question was whether his feet, or indeed his feats, big enough to fit them.

The tycoon would later describe his ownership of the business as “his greatest business coup”, although others would take a different view. His ethos was to maximise profits, and be sales orientated, rather than focusing on marketing to develop the business – perhaps an appreciation of the ‘fast buck’ over and above the prospects of sustained growth is an apt paraphrase. Despite his self-anointed success, reports suggest that by 1992, the French businessman was unable to pay the required interest to service the loans he had used to acquire the business and this, coupled with pressure to disinvest in a business that may otherwise hamper his political aspirations, led to him requesting Crédit Lyonnais to arrange a sale.