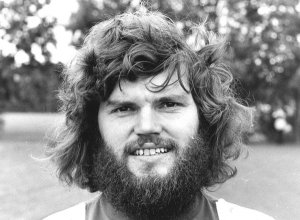

Cruyff in Oranje.

It’s often argued that for any footballer to be worthy of inclusion in the pantheon of the very greatest players of all time, as well as having success with their various clubs, they must also have excelled on the international stage, having accumulated appearances galore and delivered at the game’s most prestigious competitions. For example, Pelé made 92 appearances for the Seleção Canarinho, and played in four World Cups, winning three of them. Diego Maradona made one international appearance less than the legendary Brazilian star and also appeared in four World Cups, although only winning once, when he lifted the trophy as captain of La Albiceleste in 1986 after a dazzling individual performance. Franz Beckenbauer broke a century of appearances for the Die Mannschaft. He retired after playing 102 games for the national team. He only played in three World Cups, winning the tournament on home territory in 1974, but had also added a European Championship winner’s medal to his haul of honours, two years earlier.

With such standards to be measured against, the question arises as to how a player who appeared less than 50 times for his country – ranking at number 56 in the list of players with most appearances – played in just a single World Cup and the same number of European Championships, and never landed a single honour on the international stage, can be justifiably counted alongside the likes of Pele, Maradona and Beckenbauer as one of the true all-time greats of the game. The answer to that query is that the player in question is Hendrik Johannes Cruyff, more usually known as Johan Cruyff.

Whilst no one would contend that any of Pelé, Maradona or Beckenbauer were anything but generational talents, they each had the benefit of joining a team that had an established pedigree on the international stage. A teenage Pelé broke into the 1958 World Cup squad and, although Brazil were yet to win the trophy, runners-up in 1950 and a quarter-final appearance before losing out to the magnificent Hungarian team in 1954 illustrates that they were already among the top ranked teams in the world before he burst onto the scene. Further, after being injured in a group game in 1962, the Seleção went on to capture the trophy without him and have been crowned world champions twice more since he retired. Argentina won the World Cup without Maradona in 1978, and the Germans had won it once before Beckenbauer arrived in the team, and twice more after he had retired.

Such a pedigree of success was absent from the Dutch national team when Cruyff stepped onto the international stage on 7 September 1966. The Oranje had played in both 1934 and 1938 World Cups but had failed to win a single game, let alone progress in the tournaments. By the time they eventually made a return into football’s four-yearly jamboree in 1974, having been absent for 38 years, as David Winner states in Brilliant Orange, they had a World Cup record akin to that of Luxembourg. They had also failed to qualify for any European Champions up to that date.

In that game September 1966 game, another doomed qualifier for the 1968 European Championships, Cruyff’s debut for the Oranje was made alongside just two other players who would see action in the World Cup some eight years later. Ajax team-mate Piet Keizer appeared in just one game across the tournament, the goalless group game against Sweden, and Feyenoord skipper Rinus Israël who made a few appearances from the bench. Cruyff was hardly joining an established group of top players with a celebrated international pedigree. Yet, by the time he played his final game in Orange eight years later, the Dutch team had not only played in a World Cup Final and a European Champions and were on their way to a second successive World Cup Final, but had also been established as one of the greatest and most innovative international teams of all time. Equally, after his retirement from international football in October 1978, the Oranje would not attend a World Cup Finals for another dozen years. Typically, seven minutes after half-time in that debut against Hungary at Rotterdam’s Stadion de Kuip, he scored to put the Dutch two goals clear. Equally typically for the Oranje of the time however, two late goals from the visitors denied him a debut win.

The team was then managed by the German coach Georg Keßler who, surprisingly after the debut goal decided to drop the teenage Cruyff for the next game, a 2-1 defeat in a Friendly away to Austria. He was back however for the Friendly against Czechoslovakia in November of the same year. But, on 76 minutes, Cruyff became the first ever Dutchman to be sent off while playing for the Oranje. It led to a ban from the KNVB, which angered the already frustrated Cruyff. It wouldn’t be last time that he and the Dutch footballing authorities would cross swords. A goal on his debut and then a sending off in his second game, the scene was set for an international career that would be anything but mundane and ordinary – very much the reverse. Cruyff may not have been the only influence in such a dramatic rise in the fortunes of the Oranje but, in a 42-game career full of brilliance, bravado and bloody-mindedness in pretty much equal measure, as Brian Clough might have phrased it, he was in the top one.

Two years earlier, Cruyff had made his Ajax debut under Vic Buckingham with the English coach offering perhaps the greatest understatement of all time when he described the 17-year-old as ‘a useful kid’. It was under Rinus Michels however, who replaced Buckingham in 1965 that Cruyff’s football blossomed, with the new man at the helm quickly recognising the unique talent the club had and guiding him towards the full flowering of his abilities, before moving to Barcelona. Much as Cruyff’s influence grew with the Amsterdam club, as the years moved on and his insatiably demanding ability developed, the same would be the case with the Oranje, until the stage when he was widely considered to be a personality too large to be contained in a team environment.

The qualification campaign for the 1968 European Championships fell away, as so many others had done in the past and, when a 1-1 home draw against Bulgaria on 27 October 1969 with Cruyff absent once more, brought an end of Dutch hopes of a trip to Mexico the following year and World Cup qualification hopes were dashed once more, and Keßler’s time was all but done. The new man in charge was František Fadrhonc.

After a period of absence from the colours, the Czech-born coach selected Cruyff for a Friendly against Romania on 2 December 1970, and was rewarded with a brace from the returnee who was determined to state his case. Dutch hopes of qualifying for the 1972 European Championships were already in the Intensive Care Ward after a home draw to Yugoslavia and a defeat away to East Germany. In the next qualifier though, Cruyff bagged another brace in the six-goal romp against Luxembourg, before missing out again as qualification aspirations were all but extinguished by a defeat in Split’s Stadion pod Marjanom, when the absolute minimum of a draw was required to keep the faint hopes flickering. At the end of the group, the Dutch finished two points behind Yugoslavia, but the KNVB decided to keep faith with Fadrhonc for the campaign to reach the 1974 World Cup in neighbouring West Germany.

With Ajax now double European Cup winners and Cruyff the undisputed leader of the team and high priest of totaalvoetbal, he had also assumed the role of leading light in the national team. The qualifying programme began in May, and a 0-5 romp away to Greece, with another brace from Cruyff, set hopes rising, followed by success in a couple of Friendlies, a 3-0 win over Peru and 1-2 victory in Czechoslovakia with Cruyff opening the scoring. The qualifying group always looked likely to be a battle against Belgium for the sole qualifying spot, with the other members, Norway and Iceland, as the makeweights – and that’s how it turned out. When the two teams faced each other on 18 November 1973, they had each garnered maximum points against the group’s lesser lights, with a goalless draw in Belgium failing to offer either side much advantage. Belgium had scored 12 times without conceding, but the Dutch had doubled that figure and allowed their opponents as measly two strikes. It meant a draw was all that the Dutch needed to qualify for their first World cup in 36 years and, despite a massively controversial offside decision that ruled out a last-minute Belgian goal, they got that draw and headed across the border to West Germany.

With qualification sewn up, largely on the back of talismanic performances and seven goals across the six fixtures from Cruyff, the Ajax player was now the lead character and, accepted to be so by the KNVB who were allegedly acting under the player’s powerful influence when Fadrhonc was dismissed, despite being the first Oranje coach to get his team into the finals of a major tournament since the second World War. Cruyff’s old mentor Michels was temporarily seconded from Barcelona to take over. Before the tournament started however there were plenty more of Cruyff’s demands to be met.

Jan van Beveren had been the established first choice goalkeeper until a late season injury saw him miss the tail-end of the qualifiers with Piet Schrijvers stepping into his place. Van Beveren was one of Europe’s top stoppers and, when he regained fitness ahead of the tournament, a return to the national team looked inevitable, before a dispute with Michels saw him left out. Schrijvers looked to be the man to benefit but, reports suggest that with Cruyff pleading his case as supposed being more suitable to the creed of totaalvoetbal, Jan Jongbloed was the surprise selection between the sticks when the World Cup started. The 33-yearold FC Amsterdam goalkeeper had a mere five minutes of international experience behind him, as a late substitute a dozen yeas previously – and he had conceded in that briefest of spells. Nevertheless, with Cruyff as the driving force, the day was won and, in fairness the veteran did little to let anyone down, only conceding a single goal, and that a late own goal by Krol against Bulgaria with the game already won, before the Final when his limitations may well have been exposed.

Cruyff was also the main player in conflicts between the squad and KNVB over bonus payments and the decision to play in shirts provided by Adidas, carrying their famous three-stripe branding in black lines on the sleeves of the orange shirts. Cruyff was sponsored by Adidas’s arch-rivals Puma and refused to wear the design that had been agreed in contract by the KNVB. At first they stood firm and said the choice was theirs not the players. Cruyff countered by conceding that point but countered by asserting that the value was added by his head poking through the top of the shirt. Eventually peace was declared with a special two-striped version being provided for Cruyff. If there was any doubt who wax the first among what was surely a group of unequals, the squad numbering for the tournament told a telling tale. Numbers were allocated to the players on an alphabetical basis. The one exception being Cruyff, who was allowed to keep his number 14. For many of observers, so much of this may have looked like pandering to an inflated ego, and perhaps it was, but Cruyff’s performance in Germany justified all of that.

In the opening game against Uruguay, he pulled the strings of the Dutch attack with Johnny Rep scoring both goals that set the Oranje on their way. Four days later, the only stutter in the Dutch march towards the Final occurred when a determined, and well drilled, Sweden held them to a goalless draw. It was in this game however that Cruyff revealed the move that would carry his name for evermore. Cruyff had been drifting to the left flank of the Dutch attack on numerous occasions, allowing Rep to drift inside and seeking to unbalance the Sweden defence. When Rep played yet another wide ball to him midway through the first period, unbalanced was hardly a sufficient description for what was about to happen. Full-back Jan Olsson dutifully closed on Cruyff and, as he shaped to play the ball across field, the defender jabbed out a leg to intercept a pass that never came. Instead, Cruyff hooked the ball back between his own legs and scampered clear with Olsson looking as dumbfounded as a dupe in a conjurer’s trick. So far had he been sent the wrong way that he not only needed a ticket to get back into the stadium, he needed to hail a taxi to get back there first.

If the Sweden game had been grace, but not glory, that lack was remedied in the next game against with a comfortable 4-1 win over Bulgaria, that sent the Dutch into the second phase. The first game paired the Dutch with Argentina, and Cruyff scored twice in a 4-0 demolition of the South Americans that could been seven or eight goals had they been minded to press for them. His first goal was a mesmerising combination of athletic genius and balletic poise as he plucked a Van Hanegem pass from the air, danced around the goalkeeper and rolled the ball home. It was probably the most entrancing moment of the whole joyous Cruyff stellar performance in Germany.

A 2-0 win then eased the Dutch past East Germany and into a confrontation with Brazil Four years previously, the Seleção had produced magic of their own in winning the 1970 World Cup. This team carried the same name, but hardly the same ethics. In Germany they largely abandoned flair and style, deploying muscle and physicality rather than the grace of O Jogo Bonito. Beauty overcame the beast eventually though, and Cruyff’s goal that sealed the win on 65 minutes must surely have given him as much pleasure as any scored wearing his country’s orange shirt, albeit they wore white in that game.

And so, to the final. A game where Cruyff would be the leader of an orchestra that played sublime music, compelling the German to dance to their hypnotic tune. And yet, despite being a team of supreme talents, they lost their way and saw an early lead disappear. If anything summed up Dutch football with Cruyff, that was it. They entertained, entranced and enthused all lovers of the game, but their wings of wax melted as they flew too close to the sun. West Germany won the trophy, but Cruyff’s Oranje won the hearts of all football fans.

Michels left after the World Cup, to be replaced by the little known, and even less regarded coach George Knobel. It seemed a strange appointment to go from master coach to someone who had led MVV Maastrict, a md-table team, before taking over Ștefan Kovács’s all-conquering Ajax team. His tenure in Amsterdam would last just one season before being shown the door. It was a strange appointment and if anything, only increased the influence of Cruyff in the national team. Knobel was left as a hostage of fortune with the skills of Cruyff delivering success on the field, leaving the coach compelled to indulge his whims and wishes, or risk losing the team’s greatest asset.

The issue was perhaps best illustrated ahead of a European Championship qualifying game against Poland. By this time, Neeskens had joined Cruyff in Barcelona and the pair were granted dispensation to arrive late at training sessions due to the extra travel involved. The inch offered quickly got stretched to a mile though and, on one infamous occasion Cruyff arrived late after reportedly taking his wife shoe-shopping in Milan. As he and Neeskens arrived late for training ahead of the vital qualifier against the Poles, either Van Beveren or Willy van der Kuijlen, various accounts differ, was heard to remark “Here come the Kings of Spain.” Van Beveren and Van der Kuijlen were both PSV Eidhoven players and the number of PSV players in the squad and grown with the club’s success in the domestic game. That would do little to save them though. Whether Cruyff actually heard the remark, or it was related to him later is unclear. The upshot was however that he announced that Knobel had a choice. Either Van Beveren and Van der Kuijlen went, or he did. Unsurprisingly, Knobel bent the knee and the pair left the training camp. Other members of the PSV contingent, were initially prepared to walk out as well, but Van Beveren talked them out of it. Van der Kuijlen would later return to the fold, but the goalkeeper’s exile was much longer. Cruyff turned in a virtuoso performance. The Dutch won 3-0 and headed towards qualification. Would they have done so had Knobel backed Van Beveren and Willy van der Kuijlen and let Cruyff walk away instead? It’s one to ponder.

Sadly, the Oranje’s first venture into the truncated European Championship Finals was brief. Knobel was running out of time and respect within the squad. A row with Van Hanegem saw the Feyenoord player dropped to the bench and an ongoing dispute with the KNVB meant the semi-final against Czechoslovakia would be his last game. Cruyff was carrying an injury into the tournament and, on a wet and windy night, the Dutch lost both Neeskens and Van Hanegem to red cards and were eliminated in a sad and dispiriting performance. They went into the tournament as favourites, but such adulation ill fits with the Oranje and seldom heralds success.

There was little time for lament however. Knobel was shuffled away and the KNVB appointed Jan Zwartkruis in his place with qualifying for the 1978 World Cup under way in September. Placed in a group with Belgium, Northern Ireland and Iceland, the Dutch eased to qualification winning five of their six fixtures and drawing the other. At such times however, there is always room for unrest in the Dutch camp. Recognising the quality of Van Beveren, the new coach sought to reincorporate the goalkeeper into the squad with a sleight of hand, selecting him in the squad but not playing him in the hope that a renewed familiarity may encourage a reconciliation with Cruyff. It wasn’t to be. Frustrated by not being selected to play, Van Beveren eventually gave up the unequal struggle and officially retired from international football. He had made a scandalously low 32 appearances for the Oranje. Had merit been the sole criterion for selection, that number would surely have been doubled. Van Beveren missed out on the 1978 World Cup as, ironically, would Cruyff.

On 26 October, Cruyff featured in the 1-0 win over Belgium that completed the Oanje’s qualification programme. Few knew it at the time, but it would be his final game for the national team. Six weeks earlier, Cruyff had been sitting at home in Barcelona watching television when, what appeared to be a courier, appeared at his door. In reality, the identity of the visitor was somewhat different. Cruyff and his family had been targeted by a criminal gang seeking to kidnap Barcelona and the Netherlands star player. Fortunately, after Cruyff and his wife had been tied up, she managed to escape and raise the alarm. The culprits fled and the danger had passed. The trauma however would last much longer.

Leaving his family and travel to South America was too much a burden for Cruyff and he announced his retirement from international football. There were a number of campaigns seeking to persuade him to relent. Without revealing the true cause for his decision – he was advised by the Spanish police to keep silent about the whole affair, in case it encouraged others to repeat the attack – he was adamant. The international career of Johan Cruyff was over.

If one were to seeking to illustrate the influence of Cruyff on the national team, its fortunes before his arrival, the dramatic rise during his time in Oranje, and the decline afterwards, is evidence aplenty. Thirty-eight years absence from the World Cup were broken with two successive qualifications across a four-year spell, both of which were driven by the talismanic number 14. After 1978, the wait would stretch until 1990 before they returned. Pelé, Maradona, Beckenbauer won far more honours than Cruyff did during their international careers. Given that he won none, that would hardly be difficult. What none of that trio could say however is that arrived at a time when their teams were considered akin to the status of Luxembourg in international football terms and transformed them into, if not the best, then one of the international teams of all-time and surely the greatest never to have won a World Cup. How did that happen? It was because one of the greatest players, one with an insatiable desire to succeed and a self-belief that he could make it happen, first pulled on the Netherlands national shirt. For all of the arguments, disputes and dissent, it was a time of unheralded success. It was a time of magic. It was Cruyff in Oranje.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Cruyff’ magazine from These Football Times).

“Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe”

My seventh book – “Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe” – is published today.

Across the history of football, a select group of teams have achieved iconic status. Sometimes it’s through sheer success. For others, their stature is built by star performers. On occasions, it’s because a team has gifted a new way of playing to the world. Most rarely it’s because of all three. The Ajax teams that conquered Europe with their enthralling ‘totaalvoetbal’ are one of those rare cases. Those Dutch artists used the pitch as their canvas, the skills of the players provided a palette of gloriously bright colours and their totaalvoetbal inspired the brushstrokes that delivered masterpieces of football creativity. The Dutch Masters is the entrancing tale of how that iconic white shirt with a broad red band down its centre not only became synonymous with the beautiful game of totaalvoetbal, but also symbolised the success of the club that created a new paradigm of play. It’s the story of how Ajax came to dominate the European game as the epitome of footballing perfection.

Or visit my Amazon author page – amazon.com/author/gary_thacker – for full details of all of my books

Ulubiony Piłkarz Polski – Grzegorz Lato and the 1974 World Cup.

Although the 1974 World Cup will be remembered for West Germany lifting the trophy that anointed them champions of the world, it also marked the explosion into international consciousness of two teams, each who may have claims to being better than the tournament’s eventual winners and, who on another day could have reasonably expected to overcome the tournament hosts. Each also had an outstanding star player who many would consider the outstanding player of the tournament.

In the final, the Germans defeated the Dutch team of Cruyff and Michaels’ totaal voetbal in a game that looked destined to go the way of The Netherlands after an early goal had put the Oranje ahead, but as they spent time admiring themselves in the mirror, they got lost in their own swagger, whilst Helmut Schön’s team equalised and then snaffled the trophy away.

The other team possessing that authentic look of potential world beaters also lost to the Germans. They succumbed in the game that took the hosts into that Munich final against the Dutch. Although the denouement of a second group stage rather than a semi-final per se, the 1-0 German victory had a similar effect. The team they had vanquished was Poland, who had amongst their number the player who would be the tournament’s top scorer, and winner of the Golden Boot. If some would consider the fame duly accorded to the cult of the Dutch entirely worthy, the success of the Poles was perhaps much less celebrated. Continue reading →

The Never, Never Land of The Netherlands at the World Cup.

There’s a poignant inevitability about the fate of the Dutch national team in the World Cups played out in 1974 and 1978. Scornful of victory, embracing the creation and innovation rather than the denouement. Movement, flow and fluidity marked their way. Two losing finals; contrasting in so many ways, and yet so very similar in that both ultimately ended in shattering defeats by the tournament hosts. On the road, but not arriving. Bridesmaids donned in orange.

Widely touted as potential winners in 1974, but falling at the final hurdle despite having taken the lead when, perhaps an inherent arrogance surpassed their intoxicatingly tantalising skills. West Germany took advantage of the hubris and lifted the trophy. The Dutch shuffled away, not licking their wounds, but contemplating what might have been; off-shade tangerine dreamers. Continue reading →

The 1974 World Cup and the missing piece in Holland’s almost ‘totaalvoetbal.’

The Olympiastdion in Munich on 7th July 1974. On a seasonably warm Bavarian afternoon, the coronation of Holland’s ‘Oranje’ was expected. Rinus Michel’s team had scorched the the pitches of West Germany with the vivid bright flame of their football. The ‘Cruyff turn’ had been born when Sweden’s Olssen, bamboozled by the Dutchman’s manoeuvre not only had to buy a ticket to get back into the stadium, he also needed a taxi to get back there, so far had he been sent the wrong way. A Brazil squad, shorn of Pele for the first time in a generation had eschewed their ‘jogo bonita’ for a style some called pragmatic, others called brutal. In a beauty and the beast contest however, the Dutch had eliminated the reigning champions. Whilst the Dutch masters created flowing football with the panache of an artist, the Brazilians were cutlass-wielding barbarians in comparison. Wherever they were when they saw the performance, the souls of the ‘Pearl,’ Gerson and Tostao would surely have been uneasy. Continue reading →