“Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe”

My seventh book – “Dutch Masters – When Ajax’s Totaalvoetbal Conquered Europe” – is published today.

Across the history of football, a select group of teams have achieved iconic status. Sometimes it’s through sheer success. For others, their stature is built by star performers. On occasions, it’s because a team has gifted a new way of playing to the world. Most rarely it’s because of all three. The Ajax teams that conquered Europe with their enthralling ‘totaalvoetbal’ are one of those rare cases. Those Dutch artists used the pitch as their canvas, the skills of the players provided a palette of gloriously bright colours and their totaalvoetbal inspired the brushstrokes that delivered masterpieces of football creativity. The Dutch Masters is the entrancing tale of how that iconic white shirt with a broad red band down its centre not only became synonymous with the beautiful game of totaalvoetbal, but also symbolised the success of the club that created a new paradigm of play. It’s the story of how Ajax came to dominate the European game as the epitome of footballing perfection.

Or visit my Amazon author page – amazon.com/author/gary_thacker – for full details of all of my books

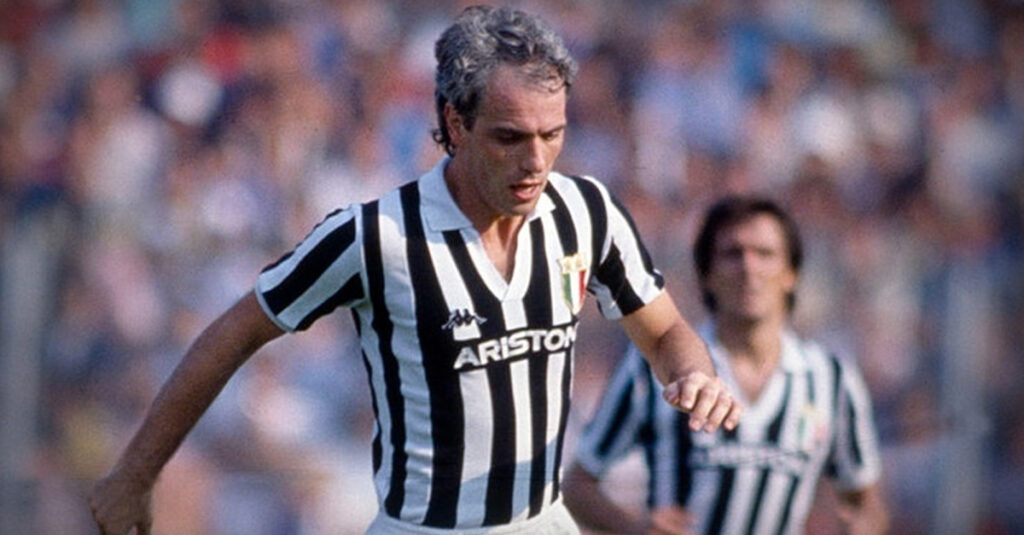

Roberto Bettega

It’s the strongest of all generational familial bonds; a mutual devotion built on the deepest of emotional attachment and respect, and one that applies nowhere more so than in Italy. The love between a mother and her favourite son endures eternally. It was the sort of bond established between La Vecchia Signora and Roberto Bettega, a child of Piedmont, born in Turin just after Christmas in 1950. For almost six decades Bettega devoted his career to I Bianconeri, first as player, and later as an administrator. Pumped by a heart of the same hue, white and black blood coursed through his veins. He even offered the Old Lady the gift of his son Alessandro, who joined the club’s youth system in 2006. Italian mommas love all of their children of course, but the ones who stay near and honour the gifts they have been given are the most treasured. That’s why there will always be a special place in the heart of La Vecchia Signora for Roberto Bettega.

The man who would become one of the most feared strikers in the history of Serie A originally fell into the embrace of the Old Lady as a young teenage midfielder in 1961, when he was accepted into the Primavera squad at the Stadio Comunale. By the beginning of the 1968-69 season, he had progressed to the first team squad. Initially elated to have reached such an exalted position whilst still in his teenage years, that joy slowly turned into frustration, granted a mere watching brief as the season ran its course without him recording his debut.

The season also brought frustration to the club, and the Juve tifosi. A fifth place Serie A finish, no less than ten points astray of champions Fiorentina, was not the standard required and the five-year reign of Paraguayan coach Heriberto Herrera was brought to an end. By now converted into a forward, Bettega was anxious to prove his with to the club and hoped the arrival of the new regime would change his fortunes. It did, but hardly in the say he had hoped. The new man in charge, Argentine Luis Carniglia, decided that there was little chance of Bettega making any meaningful contribution to the first team in the coming season, and he was sent out on loan to nearby Serie B club, Varese.

It was the sort of disappointment that could crush the spirit of an aspiring player who wanted little else than to wear the white and black stripes of his beloved Juventus. Fortunately, Bettega was made of sterner stuff and, during his time at the Stadio Franco Ossola, had the unexpected benefit of falling under the coaching of Nils Liedholm, the Swedish forward, who had enjoyed such a stellar career with AC Milan in the fifties and early sixties.

It’s difficult to discern how much Liedholm contributed to Bettega’s development, but a record of 13 goals in 30 league appearances – making him the Serie B top goalscorer – was enough to convince the Swede that here was a rare talent, about to blossom into the full flowering of an outstanding career. Knowing more than a little about what makes a great striker, Liedholm enthused about Bettega’s potential. “He is particularly strong in the air, and can kick the ball with either foot,” he commented. “All he needs is to build up experience, and then he will certainly be a force to be reckoned with.” Varese won promotion on the back of Bettega’s goals and Liedholm’s coaching. Each would later leave and go on to further, and greater, successes. Liedholm moved on Fiorentina at the end of the following season, and Bettega returned to Juventus. His CV had been stamped by Liedholm and he was ready to stake a claim for a place in the Juventus team. The timing could hardly have been better for both parties.

Whilst Bettega had been plundering goals for Varese, Juve had struggled under Carniglia and, before the end of the season, he was replaced on a temporary basis by Ercole Rabitti, with a remit to steady the ship before a new appointment at the end of the season. Rabitti stabilised the club guiding them to fifth place and qualification for the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. It was a recovery of sorts, but hardly sufficient to suggest a longer tenure, and Juve turned to Armando Picchi, the former Libero of Helenio Herrera’s all conquering ‘Grande Inter’ team. It seemed like an ideal appointment, but tragedy would deal a cruel fate for the 36-year-old who had previously coached the Azzurri. He wouldn’t see out the season. In February 1971, Picchi was diagnosed with cancer. Three months later, after a brief period in hospital had ended his coaching career, he passed away.

Bettega had made his long-awaited debut in September of 1970. His chance came in the away game against Catania and the young forward announced his arrival by scoring the winning goal. Despite that goal being his only strike before the turn of the year, it heralded more than a decade of goals that would follow in time. It wouldn’t be the last time that Roberto Bettega would please La Vecchia Signora by delivering such presents.

On 17 January, he returned to the scoresheet scoring the opening goal in a 2-1 home victory over Foggia. The elation of his first Serie A goal at the Stadio Comunale may have been just the spark to ignite Bettega. A single goal from the start of the season to the end of 1970, was followed by a dozen more before the end of the season. Following his debut goal against Catania, Bettega had waited four months to notch his second goal. After securing it against Foggia, the wait for number three was much shorter. The following week, he again scored Juve’s opening goal as I Bianconeri overcame Fiorentina 1-2 in the Stadio Artemio Franchi. The dam had well and truly been breached and on the final day of January, back at home in Turin, Bettega recorded the first hat-trick of his career in the return fixture against Catania, as Juve cantered to a 5-0 success.

The tragic fate of Picchi would, of course, cause a major problem at the club, but with Czech coach Čestmír Vycpálek promoted from the youth team to guide the club until the end of the season, a further six goals for Bettega helped the club to record a highly respectable fourth place. Bettega ended his debut season as a first team player with 13 goals and the proud record of Juve never having been beaten when he had found the back of the net.

While Rabitti’s brief tenure at the club had been insufficient to convince the club’s hierarchy that he was worthy of a permanent position, that wouldn’t be the case with Vycpálek. His ability to inspire, particularly with the younger players, whom he had worked with in his role with the youth team, held out the promise of success to come, with the goals of Bettega being a prime example. Vycpálek was given the permanent position as the club and Bettega looked forward to an exciting season to come.

Initially, the stars seemed to be perfectly aligned for Juve and, particularly for Bettega. With confidence topped up from his end of season form, an astonishing run of ten goals in his first 14 games of the new season announced to Serie A, and the wider footballing world, that the Old Lady had brought forth another outlandishly talented son. The dream start to the season would turn into a nightmare though. Early in the new year, with Juventus flying high, Bettega netted against Fiorentina. It would be his last goal until September of the same year, as ill health once again cast a dark shadow over the Stadio Comunale. This time it was their free-scoring tyro forward who fell into its malicious grasp, when a lung infection that at times threatened to turn into tuberculosis, brought his season to an end. The impetus given by Bettega’s prolific opening to the season however was sufficient to see Juve secure the Scudetto, by a single point from AC Milan.

It was a bittersweet moment for Bettega. Still only 21, the young forward had ignited the club’s revival and their first Serie A title for five years, but illness had deprived him of the joy of taking a full part in the jubilation. If he felt that fate had been less than generous to him on that occasion though, he would receive full recompense across the coming years as Juventus launched into a golden era of success and silverware, driven by the goals of Roberto Bettega, but a little patience would be asked of him first in way of payment for the glory to follow.

The champions of Italy opened the defence of their crown on 24 September 1972 with a 0-2 victory away to Bologna, and Bettega making his return to first-team action, following long months of recuperation. The result was an ideal start to the season for the club, as Franco Causio and Pietro Anastasi netted the goals. For Bettega though, although now free of the infection, the debilitating long-term effects of the illness were becoming clear, and would blight his season.

Juve would go on to retain the Scudetto by a single point from AC Milan, but it would be the goals of Causio and Anastasi – who would end the season as joint top scorers – as the prime driving force for the club. Bettega would end with just eight league goals. Juve also reached the final of the European Cup, before a timid display saw them lose to reigning champions Ajax. Bettega would start the game but be substituted at the break. Not being able to fully contribute in that game, must have felt like a microcosm of Bettega’s season.

The following season also brought frustration. Juve’s success at winning, and then retaining, the league title had made them prime targets for aspiring rivals. Vycpálek’s magic was beginning to wane and, as he chopped and changed his team in search of an elusive successful formula, Bettega’s game time was reduced. A decline in goals was an inevitable corollary. He would feature in just 24 league games, scoring eight times as the Scudetto was lost to Lazio. Vycpálek left at the end of the season, and replaced by Carlo Parola.

Parola was also a son of Turin and had appeared in more than 350 games for I Bianconeri as a redoubtable defender, very much in the style of the Italian caricature. He had won two Serie A titles, plus a Coppa Italia, and starred as the club’s captain from 1949 until leaving for a brief spell with Lazio as his playing career drew towards a close. He had also served briefly as coach on a couple of occasions a dozen or so years previously. His return would also see the league title back in Turin as Juve topped the table, two points clear of Napoli.

Once more though, whilst the club enjoyed success, Bettega’s star shone less brightly than some others. Ten goals in 47 games across all competitions was a poor return for an avowed goalscorer, but also emphasised his value to the team, even when he wasn’t finding the back of the net. It seemed that when he delivered prolific goalscoring seasons, the club would falter and, at other times, the reverse would apply. As if to illustrate that frustrating truism, as Juve lost out in the chase for the title to city rivals Torino, the following season, Bettega delivered the best goalscoring return of his career to date, scoring 18 goals in 36 games across all competitions and a highly impressive 15 in 29 Serie A games. A ratio of better than a goal in every other game in a league where excellence in defence was highly prized and almost revered as an art form was a rare achievement. Parola would leave at the end of the season.

After ascending to the first team squad in 1969, Bettega’s time as a Juventus player had seen no less than six different coaches take charge at the club. Heriberto Herrera was in place as he arrived. Luis Carniglia, and then Ercole Rabitti in the 1969-70 season. The tragic Armando Picchi had begun the 1970–1971 season before Čestmír Vycpálek took over and then Carlo Parola was appointed. Ideally, for Roberto Bettega, the next man in line would provide the elusive answer to combining seasons where both the club won silverware and the forward scored copious amounts of goals.

Giovanni Trapattoni would not only stay in post for the remainder of Bettega’s time with the club, but would also square that elusive circle of combining club success with prolific seasons for Bettega. In his first season, Juventus regained the Scudetto from Torino by a single point despite largely being a team in transition, and Bettega bettered his haul from the previous season, delivering the best goals return of his entire career.

Anastasi had now left the club and was replaced by Roberto Boninsegna. The newcomer’s partnership with Bettega would provide fearsome firepower for Juventus as they notched a combined 43 goals across all competitions. Bettega was the senior partner with 23, and Boninsegna adding 20. Just how influential the pair were is emphasised by the next highest scorers, Franco Causio and Marco Tardelli, only scoring seven each. Juve had begun like a runaway train, winning their first seven games and, in November showed that they had a steel to their game as well, recovering from two goals down in the San Siro to beat AC Milan 2-3. Bettega would net two of those three goals to lead the fightback.

Another test arrived the following month when, as nominally the away team, Torino halted Juve’s 100% record with a 2-0 in the Stadio Comunale. It put a stumble into Juve’s march but, with Bettega delivering goals aplenty they picked up the pace with the decisive game coming in April when, once again Bettega opened the scoring in a 2-1 win over Napoli. The result meant that, with three games to play, unless Juve slipped up, Torino wouldn’t be able to overhaul them. A 2-0 win away win to Inter was secured and with Bettega scoring in the next two games, the winning strike against Roma at home and then another in the game away to Sampdoria, the title was secured with Bettega’s goals being the key factor. It was a similar case in the UEFA Cup, where Juve had qualified courtesy of their runners-up position the previous season.

Juventus had disposed of both Manchester clubs in the first two rounds, but Bettega had failed to score in any of the four games. That would change in the third round though as he notched the lead-off goal in a 3-0 home win over Shakhtar Donetsk in the first leg. A 1-0 defeat in Ukraine eased Juve into the Quarter-Finals and a comfortable passage against East Germany’s Magdeburg. If anything, the Semi-Final victory against AEK Athens was even less taxing. A Bettega brace in the home leg as part of a 4-1 win had, effectively, settled matters before the return in Greece, but another goal from Juve’s main man brought a 0-1 win to confirm progress the final where Juve would face Spain’s Athletic Club. A narrow 1-0 win in Turin left things in the balance but, when Bettega scored early in the return game in Bilbao, it proved to be the decisive goal. His strikes were not only for the statisticians now, they were delivering trophies, and a total of 23 goals in 46 goals across all competitions was compelling.

When the new season opened with a 6-0 hammering of Foggia, the writing was already on the wall for Serie A. The title was retained by a more than comfortable five points. The Scudetto stayed in Turin and in the World Cup during the summer of 1978, the success of Juve was illustrated when no less than nine of the team starting against Hungary for the Azzurri were Juventus players. Bettega, of course, was one of them, and he scored.

In the following couple of seasons, the powerbase in Italian football seemed to have drifted from Turin to Milan. In 1978-79, the title went to the Rossoneri, with Juventus in third place, trailing by seven points. Success in the Coppa Italia was scant compensation given Juve’s previously dominant position. The Scudetto was then passed to fellow inhabitants of the San Siro as Inter took top spot, with Juventus three points behind in second place. Things would improve though, as Bettega continued to find the back of the net, scoring eleven and then 17 goals in each of those two seasons. The latter saw him securing the Capocannoniere award as Serie A’s top goalscorer. It seems strange that, given his consistent success over the years, that this was the first, and only, time ne would achieve that distinction.

Juventus had now gone two years without a league title and their shirts were looking a little bare without the shield that they had become do used to adorning the white and black stripes. That situation would be rectified in the 1980-81 season though, as once more Trapattoni guided I Bianconeri to the title. Injuries caused Bettega to miss a number of games, but he still contributed goals to the cause. Now moving into his thirties, the forward was compelled to adapt his style to the more cerebral and perhaps less dynamic play that age and experience both demanded and allowed.

The following season would see Juve retain the tile, but there was tragedy ahead for their star striker. Entering the European Cup, thanks to their title success the previous season, both Juve and Bettega held high hopes of continental success. The inevitable Bettega goal in a fairly comfortable passage against Celtic did little to persuade otherwise but, during the game against Anderlecht in the next round, a collision with the Belgian club’s goalkeeper was the beginning of the end of Bettega’s career with his beloved Juventus. A traumatic knee injury, with ligament damage would not only severely curtail his abilities, but also rule him out of contention for the 1982 World Cup, where fate again turned its face against him as the Azzurri won the tournament. Before the game against Anderlecht, Bettega had demonstrated that there were still goals aplenty to come. Five strikes in seven Serie A games and eight in 14 games across all competitions had put him bang on course for another prolific season. It was a level of performance that suggested he would smash his previous best goal-scoring season back in 1976-77. He would be robbed of the opportunity to deliver on that promise.

Any such injury during a player’s career can be catastrophic. By the time fitness had been regained, Roberto Bettega was 32 years old. At that age, the damage was terminal for a career built on an athleticism and technical ability now diminished by injury. It was as kryptonite to Superman. The 1982-83 season would be his last for the club. A return of just six goals from 27 games, contrasting with five from the opening seven in the previous season, bore testament to the physical damage sustained.

At the end of the season, it was clear to Bettega that his career at the top level of football was over. It was time to, at least temporarily, cut the emotional apron strings that had tied him to La Vecchia Signora. Across 13 seasons with Juventus, he made almost 500 appearances for I Bianconeri, delivering 178 goals, seven Scudetti, a Coppa Italia and a UEFA Cup. He would move to Canada and play out the dying embers of his career with Toronto Blizzard.

With his boots hung up, there would be a last return to Juventus as his old club called on Roberto Bettaga’s services once more; albeit in an entirely different sphere of activity. In 1994, club chairman, Umberto Agnelli, invited him to return to the club as vice-chairman. It was a call he willingly accepted and stayed in the role for a dozen years, sharing in more success at the club, and returning to pick up the position again for a year in 2009, before new chairman, Andrea Agnelli took control. His job had been done, family obligations completed.

There’s a special place in fans’ hearts for a one-club player and, despite brief sojourns to Varese and Canada, that was surely what Roberto Bettega was. Not only had he been one of the club’s top scorers off all time, his devotion and loyalty to the club also meant he was one of the most loved by the tifosi. There’s surely only one accolade higher and that’s to laud Roberto Bettega as a loyal and loving son to his Momma, La Vecchia Signora, the Old Lady of Turin.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Juventus’ magazine from These Football Times.