Roberto Bettega

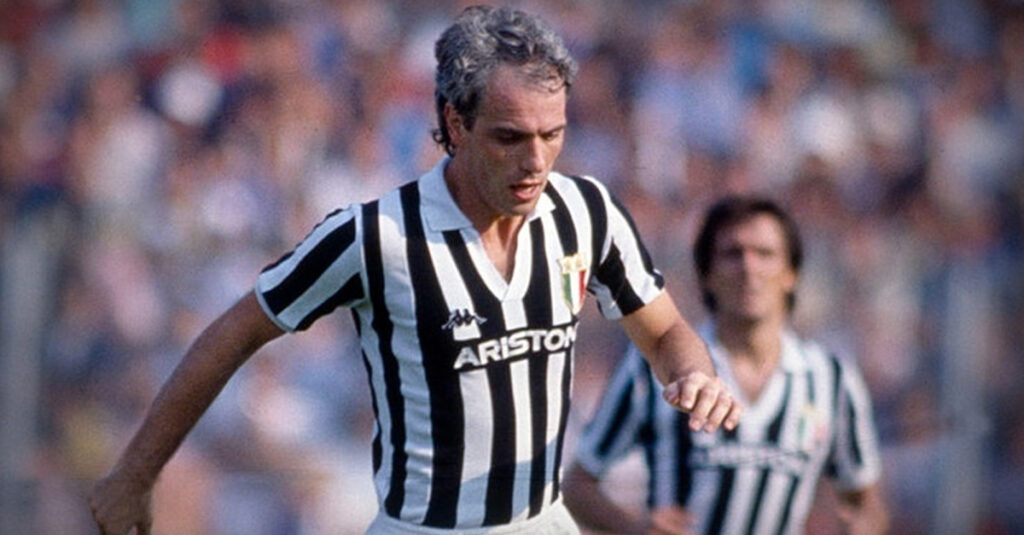

It’s the strongest of all generational familial bonds; a mutual devotion built on the deepest of emotional attachment and respect, and one that applies nowhere more so than in Italy. The love between a mother and her favourite son endures eternally. It was the sort of bond established between La Vecchia Signora and Roberto Bettega, a child of Piedmont, born in Turin just after Christmas in 1950. For almost six decades Bettega devoted his career to I Bianconeri, first as player, and later as an administrator. Pumped by a heart of the same hue, white and black blood coursed through his veins. He even offered the Old Lady the gift of his son Alessandro, who joined the club’s youth system in 2006. Italian mommas love all of their children of course, but the ones who stay near and honour the gifts they have been given are the most treasured. That’s why there will always be a special place in the heart of La Vecchia Signora for Roberto Bettega.

The man who would become one of the most feared strikers in the history of Serie A originally fell into the embrace of the Old Lady as a young teenage midfielder in 1961, when he was accepted into the Primavera squad at the Stadio Comunale. By the beginning of the 1968-69 season, he had progressed to the first team squad. Initially elated to have reached such an exalted position whilst still in his teenage years, that joy slowly turned into frustration, granted a mere watching brief as the season ran its course without him recording his debut.

The season also brought frustration to the club, and the Juve tifosi. A fifth place Serie A finish, no less than ten points astray of champions Fiorentina, was not the standard required and the five-year reign of Paraguayan coach Heriberto Herrera was brought to an end. By now converted into a forward, Bettega was anxious to prove his with to the club and hoped the arrival of the new regime would change his fortunes. It did, but hardly in the say he had hoped. The new man in charge, Argentine Luis Carniglia, decided that there was little chance of Bettega making any meaningful contribution to the first team in the coming season, and he was sent out on loan to nearby Serie B club, Varese.

It was the sort of disappointment that could crush the spirit of an aspiring player who wanted little else than to wear the white and black stripes of his beloved Juventus. Fortunately, Bettega was made of sterner stuff and, during his time at the Stadio Franco Ossola, had the unexpected benefit of falling under the coaching of Nils Liedholm, the Swedish forward, who had enjoyed such a stellar career with AC Milan in the fifties and early sixties.

It’s difficult to discern how much Liedholm contributed to Bettega’s development, but a record of 13 goals in 30 league appearances – making him the Serie B top goalscorer – was enough to convince the Swede that here was a rare talent, about to blossom into the full flowering of an outstanding career. Knowing more than a little about what makes a great striker, Liedholm enthused about Bettega’s potential. “He is particularly strong in the air, and can kick the ball with either foot,” he commented. “All he needs is to build up experience, and then he will certainly be a force to be reckoned with.” Varese won promotion on the back of Bettega’s goals and Liedholm’s coaching. Each would later leave and go on to further, and greater, successes. Liedholm moved on Fiorentina at the end of the following season, and Bettega returned to Juventus. His CV had been stamped by Liedholm and he was ready to stake a claim for a place in the Juventus team. The timing could hardly have been better for both parties.

Whilst Bettega had been plundering goals for Varese, Juve had struggled under Carniglia and, before the end of the season, he was replaced on a temporary basis by Ercole Rabitti, with a remit to steady the ship before a new appointment at the end of the season. Rabitti stabilised the club guiding them to fifth place and qualification for the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. It was a recovery of sorts, but hardly sufficient to suggest a longer tenure, and Juve turned to Armando Picchi, the former Libero of Helenio Herrera’s all conquering ‘Grande Inter’ team. It seemed like an ideal appointment, but tragedy would deal a cruel fate for the 36-year-old who had previously coached the Azzurri. He wouldn’t see out the season. In February 1971, Picchi was diagnosed with cancer. Three months later, after a brief period in hospital had ended his coaching career, he passed away.

Bettega had made his long-awaited debut in September of 1970. His chance came in the away game against Catania and the young forward announced his arrival by scoring the winning goal. Despite that goal being his only strike before the turn of the year, it heralded more than a decade of goals that would follow in time. It wouldn’t be the last time that Roberto Bettega would please La Vecchia Signora by delivering such presents.

On 17 January, he returned to the scoresheet scoring the opening goal in a 2-1 home victory over Foggia. The elation of his first Serie A goal at the Stadio Comunale may have been just the spark to ignite Bettega. A single goal from the start of the season to the end of 1970, was followed by a dozen more before the end of the season. Following his debut goal against Catania, Bettega had waited four months to notch his second goal. After securing it against Foggia, the wait for number three was much shorter. The following week, he again scored Juve’s opening goal as I Bianconeri overcame Fiorentina 1-2 in the Stadio Artemio Franchi. The dam had well and truly been breached and on the final day of January, back at home in Turin, Bettega recorded the first hat-trick of his career in the return fixture against Catania, as Juve cantered to a 5-0 success.

The tragic fate of Picchi would, of course, cause a major problem at the club, but with Czech coach Čestmír Vycpálek promoted from the youth team to guide the club until the end of the season, a further six goals for Bettega helped the club to record a highly respectable fourth place. Bettega ended his debut season as a first team player with 13 goals and the proud record of Juve never having been beaten when he had found the back of the net.

While Rabitti’s brief tenure at the club had been insufficient to convince the club’s hierarchy that he was worthy of a permanent position, that wouldn’t be the case with Vycpálek. His ability to inspire, particularly with the younger players, whom he had worked with in his role with the youth team, held out the promise of success to come, with the goals of Bettega being a prime example. Vycpálek was given the permanent position as the club and Bettega looked forward to an exciting season to come.

Initially, the stars seemed to be perfectly aligned for Juve and, particularly for Bettega. With confidence topped up from his end of season form, an astonishing run of ten goals in his first 14 games of the new season announced to Serie A, and the wider footballing world, that the Old Lady had brought forth another outlandishly talented son. The dream start to the season would turn into a nightmare though. Early in the new year, with Juventus flying high, Bettega netted against Fiorentina. It would be his last goal until September of the same year, as ill health once again cast a dark shadow over the Stadio Comunale. This time it was their free-scoring tyro forward who fell into its malicious grasp, when a lung infection that at times threatened to turn into tuberculosis, brought his season to an end. The impetus given by Bettega’s prolific opening to the season however was sufficient to see Juve secure the Scudetto, by a single point from AC Milan.

It was a bittersweet moment for Bettega. Still only 21, the young forward had ignited the club’s revival and their first Serie A title for five years, but illness had deprived him of the joy of taking a full part in the jubilation. If he felt that fate had been less than generous to him on that occasion though, he would receive full recompense across the coming years as Juventus launched into a golden era of success and silverware, driven by the goals of Roberto Bettega, but a little patience would be asked of him first in way of payment for the glory to follow.

The champions of Italy opened the defence of their crown on 24 September 1972 with a 0-2 victory away to Bologna, and Bettega making his return to first-team action, following long months of recuperation. The result was an ideal start to the season for the club, as Franco Causio and Pietro Anastasi netted the goals. For Bettega though, although now free of the infection, the debilitating long-term effects of the illness were becoming clear, and would blight his season.

Juve would go on to retain the Scudetto by a single point from AC Milan, but it would be the goals of Causio and Anastasi – who would end the season as joint top scorers – as the prime driving force for the club. Bettega would end with just eight league goals. Juve also reached the final of the European Cup, before a timid display saw them lose to reigning champions Ajax. Bettega would start the game but be substituted at the break. Not being able to fully contribute in that game, must have felt like a microcosm of Bettega’s season.

The following season also brought frustration. Juve’s success at winning, and then retaining, the league title had made them prime targets for aspiring rivals. Vycpálek’s magic was beginning to wane and, as he chopped and changed his team in search of an elusive successful formula, Bettega’s game time was reduced. A decline in goals was an inevitable corollary. He would feature in just 24 league games, scoring eight times as the Scudetto was lost to Lazio. Vycpálek left at the end of the season, and replaced by Carlo Parola.

Parola was also a son of Turin and had appeared in more than 350 games for I Bianconeri as a redoubtable defender, very much in the style of the Italian caricature. He had won two Serie A titles, plus a Coppa Italia, and starred as the club’s captain from 1949 until leaving for a brief spell with Lazio as his playing career drew towards a close. He had also served briefly as coach on a couple of occasions a dozen or so years previously. His return would also see the league title back in Turin as Juve topped the table, two points clear of Napoli.

Once more though, whilst the club enjoyed success, Bettega’s star shone less brightly than some others. Ten goals in 47 games across all competitions was a poor return for an avowed goalscorer, but also emphasised his value to the team, even when he wasn’t finding the back of the net. It seemed that when he delivered prolific goalscoring seasons, the club would falter and, at other times, the reverse would apply. As if to illustrate that frustrating truism, as Juve lost out in the chase for the title to city rivals Torino, the following season, Bettega delivered the best goalscoring return of his career to date, scoring 18 goals in 36 games across all competitions and a highly impressive 15 in 29 Serie A games. A ratio of better than a goal in every other game in a league where excellence in defence was highly prized and almost revered as an art form was a rare achievement. Parola would leave at the end of the season.

After ascending to the first team squad in 1969, Bettega’s time as a Juventus player had seen no less than six different coaches take charge at the club. Heriberto Herrera was in place as he arrived. Luis Carniglia, and then Ercole Rabitti in the 1969-70 season. The tragic Armando Picchi had begun the 1970–1971 season before Čestmír Vycpálek took over and then Carlo Parola was appointed. Ideally, for Roberto Bettega, the next man in line would provide the elusive answer to combining seasons where both the club won silverware and the forward scored copious amounts of goals.

Giovanni Trapattoni would not only stay in post for the remainder of Bettega’s time with the club, but would also square that elusive circle of combining club success with prolific seasons for Bettega. In his first season, Juventus regained the Scudetto from Torino by a single point despite largely being a team in transition, and Bettega bettered his haul from the previous season, delivering the best goals return of his entire career.

Anastasi had now left the club and was replaced by Roberto Boninsegna. The newcomer’s partnership with Bettega would provide fearsome firepower for Juventus as they notched a combined 43 goals across all competitions. Bettega was the senior partner with 23, and Boninsegna adding 20. Just how influential the pair were is emphasised by the next highest scorers, Franco Causio and Marco Tardelli, only scoring seven each. Juve had begun like a runaway train, winning their first seven games and, in November showed that they had a steel to their game as well, recovering from two goals down in the San Siro to beat AC Milan 2-3. Bettega would net two of those three goals to lead the fightback.

Another test arrived the following month when, as nominally the away team, Torino halted Juve’s 100% record with a 2-0 in the Stadio Comunale. It put a stumble into Juve’s march but, with Bettega delivering goals aplenty they picked up the pace with the decisive game coming in April when, once again Bettega opened the scoring in a 2-1 win over Napoli. The result meant that, with three games to play, unless Juve slipped up, Torino wouldn’t be able to overhaul them. A 2-0 win away win to Inter was secured and with Bettega scoring in the next two games, the winning strike against Roma at home and then another in the game away to Sampdoria, the title was secured with Bettega’s goals being the key factor. It was a similar case in the UEFA Cup, where Juve had qualified courtesy of their runners-up position the previous season.

Juventus had disposed of both Manchester clubs in the first two rounds, but Bettega had failed to score in any of the four games. That would change in the third round though as he notched the lead-off goal in a 3-0 home win over Shakhtar Donetsk in the first leg. A 1-0 defeat in Ukraine eased Juve into the Quarter-Finals and a comfortable passage against East Germany’s Magdeburg. If anything, the Semi-Final victory against AEK Athens was even less taxing. A Bettega brace in the home leg as part of a 4-1 win had, effectively, settled matters before the return in Greece, but another goal from Juve’s main man brought a 0-1 win to confirm progress the final where Juve would face Spain’s Athletic Club. A narrow 1-0 win in Turin left things in the balance but, when Bettega scored early in the return game in Bilbao, it proved to be the decisive goal. His strikes were not only for the statisticians now, they were delivering trophies, and a total of 23 goals in 46 goals across all competitions was compelling.

When the new season opened with a 6-0 hammering of Foggia, the writing was already on the wall for Serie A. The title was retained by a more than comfortable five points. The Scudetto stayed in Turin and in the World Cup during the summer of 1978, the success of Juve was illustrated when no less than nine of the team starting against Hungary for the Azzurri were Juventus players. Bettega, of course, was one of them, and he scored.

In the following couple of seasons, the powerbase in Italian football seemed to have drifted from Turin to Milan. In 1978-79, the title went to the Rossoneri, with Juventus in third place, trailing by seven points. Success in the Coppa Italia was scant compensation given Juve’s previously dominant position. The Scudetto was then passed to fellow inhabitants of the San Siro as Inter took top spot, with Juventus three points behind in second place. Things would improve though, as Bettega continued to find the back of the net, scoring eleven and then 17 goals in each of those two seasons. The latter saw him securing the Capocannoniere award as Serie A’s top goalscorer. It seems strange that, given his consistent success over the years, that this was the first, and only, time ne would achieve that distinction.

Juventus had now gone two years without a league title and their shirts were looking a little bare without the shield that they had become do used to adorning the white and black stripes. That situation would be rectified in the 1980-81 season though, as once more Trapattoni guided I Bianconeri to the title. Injuries caused Bettega to miss a number of games, but he still contributed goals to the cause. Now moving into his thirties, the forward was compelled to adapt his style to the more cerebral and perhaps less dynamic play that age and experience both demanded and allowed.

The following season would see Juve retain the tile, but there was tragedy ahead for their star striker. Entering the European Cup, thanks to their title success the previous season, both Juve and Bettega held high hopes of continental success. The inevitable Bettega goal in a fairly comfortable passage against Celtic did little to persuade otherwise but, during the game against Anderlecht in the next round, a collision with the Belgian club’s goalkeeper was the beginning of the end of Bettega’s career with his beloved Juventus. A traumatic knee injury, with ligament damage would not only severely curtail his abilities, but also rule him out of contention for the 1982 World Cup, where fate again turned its face against him as the Azzurri won the tournament. Before the game against Anderlecht, Bettega had demonstrated that there were still goals aplenty to come. Five strikes in seven Serie A games and eight in 14 games across all competitions had put him bang on course for another prolific season. It was a level of performance that suggested he would smash his previous best goal-scoring season back in 1976-77. He would be robbed of the opportunity to deliver on that promise.

Any such injury during a player’s career can be catastrophic. By the time fitness had been regained, Roberto Bettega was 32 years old. At that age, the damage was terminal for a career built on an athleticism and technical ability now diminished by injury. It was as kryptonite to Superman. The 1982-83 season would be his last for the club. A return of just six goals from 27 games, contrasting with five from the opening seven in the previous season, bore testament to the physical damage sustained.

At the end of the season, it was clear to Bettega that his career at the top level of football was over. It was time to, at least temporarily, cut the emotional apron strings that had tied him to La Vecchia Signora. Across 13 seasons with Juventus, he made almost 500 appearances for I Bianconeri, delivering 178 goals, seven Scudetti, a Coppa Italia and a UEFA Cup. He would move to Canada and play out the dying embers of his career with Toronto Blizzard.

With his boots hung up, there would be a last return to Juventus as his old club called on Roberto Bettaga’s services once more; albeit in an entirely different sphere of activity. In 1994, club chairman, Umberto Agnelli, invited him to return to the club as vice-chairman. It was a call he willingly accepted and stayed in the role for a dozen years, sharing in more success at the club, and returning to pick up the position again for a year in 2009, before new chairman, Andrea Agnelli took control. His job had been done, family obligations completed.

There’s a special place in fans’ hearts for a one-club player and, despite brief sojourns to Varese and Canada, that was surely what Roberto Bettega was. Not only had he been one of the club’s top scorers off all time, his devotion and loyalty to the club also meant he was one of the most loved by the tifosi. There’s surely only one accolade higher and that’s to laud Roberto Bettega as a loyal and loving son to his Momma, La Vecchia Signora, the Old Lady of Turin.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Juventus’ magazine from These Football Times.

Baggio and AC Milan – The star-crossed relationship doomed to fail.

There comes a time in most players’ careers when their club sees them as surplus to requirements. Sometimes that can occur when there’s a perception that age has blunted their skills and a younger player seems to offer a better return on investment, or when there’s an apparent mismatch between the coach’s vision for the squad and the talents the player can offer. At other times, it can simply follow a fall out between player and club. On some rare occasions, it’s a combination of all three – with a little extra spice thrown in as well.

At the end of the 1994-95 season Roberto Baggio had reached that precise situation with Juventus. It had been Baggio’s fifth season living with Turin’s Old Lady, and the most decorated. He had joined Juve from Fiorentina in 1990 and collected a UEFA Cup winner’s medal in 1993, as I Bianconeri comfortably overcame Borussia Dortmund 6-1 on aggregate with Baggio netting one of the half-dozen goals. In 1994-95 however, Juve surpassed that achievement with something to spare, establishing domestic domination by securing the Italian domestic double of winning the Scudetto and the Coppa Italia. Sadly, for Baggio, despite collecting a couple of winner’s medals, his on the field contribution to the triumphs had been restricted, featuring in only 17 of the club’s Serie A games and not featuring at all in Copa Italia Final.

By now, it had become increasingly clear to Baggio that he would be unlikely to significantly figure in any success the club enjoyed moving forwards. Coach Marcello Lippi had transferred his affections to the prodigious young talent of Alessandro Del Piero, now in his major breakthrough season at the club. Across each of the previous four seasons, Baggio had featured in more than 40 of the club’s games, but the emergence of Del Piero had flattened that off to a mere 29 in the 1994-95 term, with the youngster playing in 50. At 28 years of age, Baggio was probably still in his peak years, but Del Piero was seven years younger and, from the club’s point of view, held greater long-term value. If not exactly willingly passed on, the baton had been removed from Baggio’s hand, and given to Del Piero, and the club’s domination of Italian football only emphasised the accepted wisdom of the move.

The Juventus management had already informed Baggio that the only way they would consider a new contract for him was if he agreed to a 50% cut in his salary, and a reduced role within the squad. It hardly led to cordial relations between Baggio on one side and Lippi, Luciano Moggi and Umberto Agnelli on the other. A parting of the ways was inevitable and, with the announcement from the club that the number ten shirt would be worn by Del Piero for the new season, the final nail was driven home.

If being shown the door by Juventus was inevitably an unwelcome turn in Baggio’s career, there were plenty of other suitors lined up and willing to pay the required fee to secure his services. In England, as ever, Manchester United were among the club’s linked with one of the established stars of European football. After all, this was just one season after Baggio had starred for the Azzurri on the football world’s biggest stage at the World Cup in the USA and, as the BBC’s Stefano Bozzi stated, “single-handedly hauled Italy to the final.”

Blackburn Rovers had just secured their first league title for more than 80 years and, funded by the largesse of Jack Walker, sought to bring the Italian maestro to Ewood Park to cement their arrival in the big time.

In Spain, La Liga champions Real Madrid looked to take the player to the Bernabeu, adding Baggio to a squad already boasting the talents of Butragueño, Zamorano, Fernando Redondo, Michael Laudrup and Raul. President Ramón Mendoza was entering the final few months of his decade heading the club and delivering Baggio would have been an ideal parting gift to the Madridistas, but it wasn’t to be. Both Milan clubs were also interested and, eventually it was the persuasive pressure of Silvio Berlusconi and manager Fabio Capello that won out, with the Rossoneri agreeing a reported £6.8 million fee to take Baggio to the San Siro.

After initially struggling with early season injuries – a propensity to injury was a stick that his critics repeatedly used to beat him with as his career progressed – Baggio enjoyed a successful first period with the Milanese club and it fell to him to strike a penalty to win the game against his former team Fiorentina in the game that decided the Scudetto would be adorned with red and black ribbons for that season. Securing the title by a clear eight points from Juventus in the runners-up spot must have carried an extra level of satisfaction of Baggio. For much of the season, with George Weah as the lone striker supported by Baggio and Savićević, Milan were a potent attacking force.

In raw statistics, his seven goals in Serie A games netted during his first term in Milan hardly speak of a huge influence, but the contribution of players such as Baggio transcend mere statistics. His influence on the field and perceptive play created numerous chances for his team-mates, as is suggested by the 12 ‘official’ assists he recorded in that season. It was the highest in Serie A. Much as with the fans at Juventus, the tifosi on the Curva Sud took Baggio, their new fantasista, snaffled away from rivals in Turin, who had brought the Scudetto with him, to their hearts. As the fans in Turin must have lamented losing Baggio, he was acclaimed in Milan as the fans voted him their player of the season.

Even before the season was out however, cracks in the relationship between Baggio and Capello began to develop. The coach, who was in his last season at the San Siro before briefly moving on to Spain and Real Madrid, was the hardest of taskmasters and his strict patterns of play left little room for the flamboyant skills and ‘street football’ talents of Baggio. The Curva Sud adored him but, for a time, Capello merely tolerated him.

In such a relationship the coach, especially one with such a list of achievements with the club, would always win. As the season wore on, Baggio’s playing time became increasingly curtailed. Capello cited the old chestnut of the player having fitness issues, and being unable to perform at the required level for a full 90 minutes. It was something that Baggio contested, but without being able to change the coach’s stance. In his 28 Serie A appearances during the season, he would only play the complete 90 minutes on seven occasions. He was substituted in the second period on 16 occasions, and took to the field from the bench twice. As with Juve’s successful season when integrating Del Piero into their team ahead of Baggio, titles talk, and Capello delivering the Serie A title left little room for Baggio’s disappointments to gain ground with the club’s hierarchy.

The following season, Uruguayan coach Óscar Tabárez replaced Capello as Milan sought to build on their title success. For both club and Baggio however, the appointment heralded a difficult time. If Capello’s authoritarian ways had rubbed painfully up against Baggio’s style, the pragmatism of the new man on Milan’s bench hardly saw an improvement. The coach’s oft-referenced statement that “There is no place for poets in modern football,” hardly suggested a meeting of minds between coach and player, a situation that was played out a Baggio began the new season occupying the bench more often than not, a scenario that a perplexed Zinedine Zidane described as “something that I will never understand in my lifetime.”

Through dedication and applied determination when granted playing time however, Baggio’s ability eventually won over the coach and as the season progressed, he was increasingly deployed, either in his favoured position playing behind Wear, or less effectively shunted out to a wide position on the left flank.

In September, following their league title win the previous season, and with Baggio now settled into the starting eleven, Milan began their Champions League campaign placed in a group also comprising Porto and the Scandinavian pair of Rosenborg from Norway and Sweden’s IFK Göteborg. Strongly fancied to fill one of the top two places alongside Porto, Milan opened their campaign on 11 September at home to the Portuguese club. Despite twice taking the lead however, a late goal by Jardel gave the visitors a 2-3 win, and Milan suddenly had a mountain to climb.

Two weeks later, things looked to have improved with a 1-4 win in Norway, but Baggio had been relegated to the bench and didn’t feature. By the middle of October, when Milan lost 2-1 in Göteborg despite leading from a Weah goal, he didn’t even make the bench. Two weeks later, he came off the bench to face the same opponents with Milan holding a narrow 3-2 lead and scored the fourth goal – his first in European club football’s premier competition to steer Milan safely over the line.

With two games remaining, away to Porto and then home to Rosenborg, avoiding defeat in Portugal and then winning against the Norwegians in the San Siro offered a surely achievable passage into the quarter-finals. A 1-1 draw against Porto, on 20 November with Baggio starting but replaced for the final dozen minutes or so looked to have seen the more difficult of the two tasks achieved. Less than two weeks later though, with domestic form falling away, the Berlusconi axe fell. In the early days of December 1996, with the club only having won eight of their first 22 games, the president decided that the Uruguayan was not up to the task of replacing Capello, and moved to secure the services of previous coach, and the man who led the Azzurri into the World Cup in 1994, Arrigo Sacchi.

To outsiders, the prospect of reuniting Baggio with the coach of the Italian team that he had starred in during the tournament in the USA looked an exciting proposition. As with so many of his coaches however, Baggio had experienced an uneasy relationship with the national team’s coach, and their relationship had been often tepid, and occasionally frosty.

The situation at the San Siro however, demanded a reconciliation for the good of all concerned and the new coach sought to exploit the potential of Baggio offering him both encouragement and playing time. The ploy faltered however. Perhaps due to the inconsistent and differing coaching and tactical requirements of playing under three different coaches in eight months or so, a loss of form, or the general malaise sweeping through the squad, the magic in Baggio’s boots dimmed and Milan’s season deteriorated.

Sacchi’s first game was the decisive group encounter against Rosenborg. Strong favourites to win and qualify, the new coach started with Baggio in the team. At half-time however, with only a last-minute equaliser from Dugarry getting Milan into the dressing room on level terms, Sacchi withdrew Baggio in favour of Marco Simeone. It was to little avail however as a 70th minute strike by Vergard Heggem condemned the Rossoneri to a humiliating defeat, and elimination.

After winning the Scudetto the previous season, a mid-table eleventh position, elimination in the quarter-finals of the Coppa Italia – ironically at the hands of Baggio’s former club Fiorentina as the player sat frustratingly on the bench – and a chastening experience in Europe was a shuddering disappointment, and something not to be tolerated by the eternally demanding and impatient Berlusconi.

The summer saw not only the end of Sacchi’s brief return spell and Capello’s return to the San Siro, but also the exit of Baggio. Never truly convinced of Baggio’s worth to any squad organised along the lines that he insisted his team’s follow, Capello declared that the player would not be part of his plans for the new season. It was time to move on.

Baggio’s initial choice was a move to Parma but, as was becoming a recurring theme in his career, the Parma coach, Carlo Ancelotti persuaded the club not to pursue the transfer as he felt the player would not fit into his tactical planning, then set as a rigid 4-4-2. It was a decision he would later admit to regretting, but at the time, it eliminated Parma from Baggio’s options and instead he moved to Bologna.

In his two seasons at the San Siro Roberto Baggio would feature in 67 games for the Rossoneri, 61 of them in Serie A. He would score 19 goals, of which a dozen came in the league. He would also contribute numerous unrecorded assists and apply a creative touch to the club’s attacking play often only best appreciated by the fans on the Curva Sud, rather than the coaches sat on the bench. He collected a Serie A winner’s medal and played Champions League football for the first time in his career, and yet there remains a sense of unfulfilled destiny.

Leaving Juventus to join Milan hardly looked like a step down, something illustrated by the club’s league success during in his first season, but there surely should have been so much more to follow. So many players of outrageous talent have fallen foul of a coach’s lack of ability to integrate such magical talents into their team. Throughout his career, this scenario blighted the career of Roberto Baggio, but perhaps never more so than during his time with Milan.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘Baggio’ magazine issue from These Football Times).

John Charles – The Gentle Giant.

Two days after Christmas in 1931, the Charles family of 19 Alice Street in the Cwmbwrla district of Swansea had their second child. As the family grew, he would go on to be the eldest of three sons, and second eldest of five children born to Ned Charles and his wife Lilian. A younger son, Mel would go on to become a professional footballer, play at the highest club level in Britain, and represent Wales on the international stage, including at the World Cup of 1958 in Sweden. It’s an impressive pedigree, and yet Mel was only the second most famous son to emerge from that house in Alice Street. The boy who was born on that late December cold winter day in 1931 would also turn to professional football and carve out a career in Britain and abroad that would make him a legend of the game and forever written into the annals of Leeds United. His name was John Charles.

Charles was educated at the local Cwmdu Junior School and, when he at the age of 14, his burgeoning talent as a footballer had already been recognised by Swansea Town, then in the third tier of the English league pyramid, who signed him to their ground staff. With the physique of someone many years older, and a natural football ability, he was marked out for great progress, but the reality of his tender years made the club reluctant to push him too far too quickly, and he never graduated to the club’s first team. A number of appearances for the club’s Reserve team, competing in the Welsh Football League was the limit of his progress at the Vetch Field. Others would not be so reluctant to give the titan of a youngster the opportunity to prove that old footballing maxim that ‘if you’re good enough, you’re old enough’.

Gendros is another area of Swansea, half a mile or so from Cwmbwrla, and Charles played for a youth club team there. At 17, he was spotted by Jack Pickard, a scout for Leeds United, and invited for a trial with the Yorkshire club. It took little time to impress the coaching staff at Elland Road and Charles moved to Leeds. The one bone of contention for the club, at the time merely a fairly modest second tier outfit, was where the Welsh tyro should play. Such was the talent of the teenager that every position he was tried in – full back, centre-half, wing-half and even centre-forward – seemed well within Charles’s compass of ability to excel at.

At the time, the club was managed by the legendary Major Frank Buckley and, after reviewing the performances of the Welsh teenager in a variety of positions, across a number of reserve team games, he decided to give Charles his first team debut as a centre half. The game chosen to launch the untapped talents of John Charles upon an unsuspecting footballing world was a Friendly against Scottish club Queen of the South, on 19 April 1949.

Three weeks earlier, Scotland had visited Wembley for a Home International fixture, and returned with a convincing 1-3 victory in front of 98,000 spectators. An England defence captained by Billy Wright and also comprising Neil Franklin, Jack Aston and Jack Rowe had been tormented by the Scots, and especially their centre forward Billy Houliston. It would be the task of the novice centre half, John Charles, to harness Houliston and achieve something

that Wright, and similar luminaries of the English game had failed to do weeks earlier. The game ended in a goalless draw and, afterwards, a frustrated Houliston would remark that Charles was “the best centre half I’ve ever played against”. He wouldn’t be the last forward to voice that assessment across the coming years.

To no one’s great surprise, Charles was retained at the heart of the Leeds defence for the following Saturday, and a league game against Bristol Rovers at Elland Road. Another blank for the Yorkshire club’s opponents added the nascent belief that Leeds had a rare talent on their hands. There were two league games remaining to play out the season and Charles featured in both of them. In the summer, Tom Holley, the erstwhile stalwart centre half and skipper of the team of the team, recognised the reality of the changed situation, and retired from the game to pursue a career in journalism. John Charles had quickly made the elder man redundant and established himself as a key element in the Leeds team. In his new guise, Holley would later write of Charles. “Nat Lofthouse was asked who was the best centre half he had played against and without hesitation named John Charles. The same week, Billy Wright was asked, who was the greatest centre forward he had faced, and he again answered John Charles.”

The following term Charles played every game in Leeds’s campaign, establishing himself as an outstanding defender and on 8 March 1950, his talents were recognised by the Wales national team when he made his debut for the country in a Home International fixture against Northern Ireland at Wrexham. Needless to say, the visitors failed to find a way past Charles and his fellow defenders, with the game ending in a goalless draw. He was still only 18 years of age, and had become the youngest player ever to represent Wales. It’s a record that stood for more than four decades, until broken by Ryan Giggs in 1991.

From 1950 until 1952, Charles completed two years of National Service with the 12th Royal Lancers, based in Carlisle. The journey was hardly a simple matter but he was allowed to travel back to Yorkshire to play for Leeds as well as fulfilling his duty by turning out for his regimental team that went on to win the Army Cup in 1952 with Charles captaining the team and lifting the trophy. The same period also saw his time on the pitch limited by two cartilage operations.

It was a time when Leeds began to take regular advantage of the versatile nature of Charles’s talents. With the club struggling to find the back of the net with any consistent reliability, Charles was pushed forward into the centre forward position. In October 1952, the move produced instant dividends, with 11 goals in six games. The move had worked but, at the same time, it also illustrated the growing dependence the club had on the young Welshman as, in his absence, the previously almost watertight defence was shown to have as many leaks as a colander. It meant a number of changes between front and back for Charles – often within a game – but he coped admirably and Leeds profited. In a number of games, he would begin as a forward, Leeds would establish a lead on the back of his talents, and then he would be switched back into defence to hold on to the advantage. It sounds like a strange, and somewhat unreal scenario, but it worked and, years later Juventus would adhere to the same formula in Serie A, with spectacular success.

In 1953-54 season, Charles was given an extended run at centre forward and netted an impressive 42 league goals in just 39 games. It was a club record haul and the remarkable strike rate made him the top scorer in the division. He was still in his early-twenties, but now unmistakably the most important, and potent, weapon at the Elland Road club. Inevitably, the Welshman’s success was also beginning to draw admiring glances from both First Division clubs and even abroad, such was the fame of his exploits. Understandably, Charles was keen to progress his career and a desire to play at the highest possible level fed his ambition.

In 1955, he was appointed as club captain and led the club to runners-up spot in the Second Division and promotion to the top tier of English football. His 29 goals, in the 1955-56 season, as an ever-present across the 42-game league programme, was a key factor in the club’s success. Now at the top level of the English game, there were hopes among the Leeds hierarchy and fans that Charles’s ambition would be sated for a while and, conversely perhaps what would surely be less success for the player in the top tier may dissuade any potential suitors. It was a forlorn hope.

Promotion for any club can lead to a difficult initial period as players struggle to come to terms with the increased demands of higher-level competition, but for John Charles, this was hardly the case. Leading from the front the Welshman scored 38 goals in 40 league appearances establishing a record for the club in top flight competition, as Leeds finished in an impressive eighth position. By now, Buckley had been replaced by Raich Carter as manager of Leeds United, but there was only one man who was recognised as the most important asset of the club, and that was John Charles. In some newspapers, Leeds were even referred to as John Charles United. It was perhaps an exaggeration of his value to the club but, if so, only a slight one. Any doubts as to whether John Charles could deliver at the highest levels had already been brought into doubt with his performances for Wales – but his debut season in the First Division not only dispelled any lingering doubts, it also inevitably intensified interest in him from other clubs.

The white-hot heat of the John Charles talent was simply too hot for Leeds to hold onto, and a deal was agreed with Italian giants Juventus for him to move to Turin at the end of the 1956-57 season for a world record fee of £65,000. In his final game for Leeds before departing for Italy, they faced Sunderland on 22 April 1957. In what was somewhat inevitably a hugely emotional game, Charles scored twice in 3-1 win to sign off his time at Elland Road. He had scored 157 goals in 257 games for the club, many of them coming from a defensive position. John Charles had joined Leeds United as a young promising teenager with potential as yet undiscovered. At 26 years of age, he left for Italy as the most valuable footballer on the planet. Tall and muscular, but with abundant skill coupled and irresistible determination, quite simply put, John Charles was one of the best footballers ever to draw breath, and comfortably the most complete talent to arise from the British Isles at the time. Years later, Sir Bobby Robson, a playing contemporary of the Welshman would eulogise on the talents of John Charles. “Where was he in the world’s pecking order? He was right up there with the very, very best. Pele, Maradona, Cruyff, Di Stephano, Best. But how many of them were world class in two positions? The answer to that is easy: None of them.”

In five years with Juventus, John Charles became a legend with the Turin club. The practise first deployed by Major Buckley, years earlier, of selecting Charles to play as a forward until a sufficient lead was established, before dropping him back to defend was turned into a fine art at the club and, of course he netted the winner in his debut for La Vecchia Signora in a 3-2 victory over Hellas Verona. His first season in Italy saw him become Serie A’s top scorer as Juventus won the Scudetto. It set a pattern. Together with Omar Sívori and Giampiero Boniperti, Charles formed what quickly became known as The Holy Trident as two more league titles followed, together with a brace of Coppa Italia tirumphs. The esteem that the fans had for Charles in Turin was exemplified when, in 1997 at the club’s centenary, the Welshman was voted as Juventus’s best ever foreign player.

In 1962, Don Reive, now in charge at Elland Road and seeking to build the club agreed a record fee of £53,000 to take Charles back to Elland Road. The move caused such excitement among supporters that admission fees were increased for the start of the new season. There’s an old adage in football though that you ‘should never go back’. John Charles was now past his thirtieth birthday and although much of the skill and physical prowess remained, five seasons in Europe’s toughest league had inevitably taken its toll and despite typical application to the cause, it was doomed to fail. Eleven games and three goals were a poor return on the investment and it quickly became clear to the player that, after years of the Italian lifestyle, a return to the British way of life was a bridge too far. Leeds agreed a fee with Roma that would give them a nominal profit on the money given to Juventus, and John Charles returned to Italy.

After once more scoring on his debut, his time in Rome was almost as short as that on his return to Yorkshire. Further moves followed, first back to Wales and Cardiff City – joining younger brother Mel – then to non-league Hereford United in a short period as Player-Manager, before going back to Wales and Merthyr Tydfil and eventually retiring in 1974. He passed away in 2004, aged 85. Perhaps it was appropriate that, in the end, his final illness struck him while in Italy, where had been invited to work as a television pundit. Juventus quickly offered to pay the costs to get him back to Britain alongside his wife, two doctors and a nurse. At 4.30pm on 21 February 2004, at Pinderfields Hospital, he passed away.

A ball boy for Juventus during the great days of Charles’s Italian adventure with Juventus, Roberto Bettega was now president of the club. Speaking after news of the death, his words were for the fans of Juventus, but they would echo the sentiments of the fans who worshipped Charles at Elland Road. “We cry for a great champion, and a great man. John is a person who interpreted the spirit of Juventus in the best possible manner and represented the sport in the best and purest manner.” Never cautioned or sent off in his entire career, it was a fitting tribute.

Jack Charlton, another of the great Leeds United defenders, and someone who inherited the shirt left by Charles had little doubt about where the Welshman should be ranked among the pantheon of the world’s greatest players, and why. “I had just arrived at Elland Road and they were all talking about John Charles,” Charlton recalled. “He was quick, he was strong, and he could run with the ball. He was half the team in himself. He was tremendous.” But there was to Charles than that. “John Charles was a team unto himself,” Charlton explained. “People often say to me, ‘Who was the best player you ever saw?’ and I answer that it was probably Eusébio, Di Stéfano, Cruyff, Pelé or our Bob (Bobby Charlton). But the most effective player I ever saw, the one that made the most difference to the performance of the whole team, was without question John Charles.” It’s an entirely apt and accurate description. In a period that saw Leeds United rise from being a mediocre second tier club, to one established in the top rank of English football, the overwhelming reason was the emergence and development of John Charles, the boy who came from the Welsh valleys to become a Leeds United legend.

(This article was originally produced for the ‘These Football Times’ Leeds United magazine).

“Aeroplinino!” Vincenzo Montella.

Born in Pomigliano d’Arco in the Naples province of Italy in June 1974, Vincenzo Montella always dreamt of being a professional footballer, of playing in Serie A. Although during his childhood days, a natural shortness of stature often saw him relegated to the role of goalkeeper, he would mature into the rapacious predator type of forward esteemed by Italian football fans, and a legend for the tifosi of Roma’s Curva Sud in the Stadio Olimpico. In his time with I Giallorossi, Montella would score just short of a century of goals, and each would be marked with his trademark celebration, arms stretched wide, mimicking an aeroplane. The fans celebrated once more as their joy took flight, thanks to their ‘little airplane.’ Continue reading →

Patrick Vieira – From AC Milan’s Reserves to Premier League Invincible.

After being signed from Cannes, where he debuted for the club at 17, and was captain two years later, Patrick Vieira’s career seemed to be heading into the buffers at AC Milan. He joined the club in the close season of 1995, and twelve months later, he had made just two first team appearances with most of his time being spent with the reserves. Continue reading →

Paul Lambert – Forever the Scottish brick in Dortmund’s Yellow Wall

For any footballer at a mid-ranking club, bereft of the sort of the perceived talent and reputation that attract admiring clubs like moths to a light, and a defunct contract, there’s an obvious fork in the road. To the right lies the safe path. Your club wants to offer you a new deal. It’s safe. It’s guaranteed. It means you can still provide for your family. The other road – the one leading to all sorts of left field possibilities – is solely reserved for the brave, or the foolhardy. It leads to, well that’s the whole point. You simply don’t know where it leads, and if your briefly itinerant excursion into the exploration of the unknown is a dead end, there’s no guarantee that you can retrace your steps and opt for the other road afterwards.

Such a choice faced Motherwell’s Scottish midfielder Paul Lambert, at the end of the 1995-96 season. Lambert chose left path, having “…always wanted to try to play abroad.” As he later remarked, “I had nothing to lose at the time and never knew how things were going to pan out.” Sometimes the right path is the wrong path. Lambert chose left and twelve months later with a Champions League winner’s medal in his pocket after a Man of the Match performance negating the talents of Zinedine Zidane, no-one was questioning his sense of direction. Continue reading →

“If you can meet with triumph and disaster. And treat those two impostors just the same.” Arsenal’s testing four days in May 1980.

Using that particular quote from Kipling is a well-trodden path and, to illustrate its relevance, I’ll lean a little on another master of words, Oscar Wilde, whilst at the same time apologising for mangling his famous couplet, ‘to lose one cup final may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.’ Across four testing days in May 1980 however, that’s precisely what happened to Arsenal. Continue reading →